“What is my purpose in life?”

The question is so common, it’s cliché. But many people will die without an answer, regardless of the earnestness or persistence with which they pursue it.

Maryanne, however, stopped asking that question twenty years ago. She knew her purpose. And her place. While she was living in the Catholic convent in New Jersey, she called an old friend and said, “I’m not sure if we’re supposed to find our place this side of heaven, but if we are, I’ve found it.”

The sister’s habit, which was designed to be as impersonal as an army uniform, felt like it was designed for her alone. Even the title “Sister” seemed like a natural part of her name.

“Even before I was called to religious life, I had a longing for something more,” Maryanne said. “Before I became a sister, when I was just going to the convent and experiencing that life, that longing feeling disappeared. It was gone. I had found my place. I was born a female for this reason. I was going to become a sister. My life was going to totally belong to Jesus and nobody else, and he was going to be my everything.”

But even with the strength of her prayers, her certainty, and her conviction, her calling was harder to maintain than to attain. And it was pain, finally, that caused her to stray from the once-clear path.

“I was there eight years. I entered at thirty-two, celebrated my fortieth birthday, and left that June. The day I left the convent, that longing feeling came back, and it’s been there ever since.”

Primed to Hear the Call

Maryanne grew up in Newark, New Jersey, near the Jersey Shore. Her Italian-American parents embraced Catholicism as part of their ethnic heritage, but they weren’t particularly devout. Maryanne was the same, at first. As a young woman, she went to Mass on Sundays, but wasn’t terribly interested in theology or concerned about the ethical debates.

But in her early twenties, Maryanne had a change of heart. One day, while in Mass, she felt a need she couldn’t define well up within her. She wanted to be part of something greater. She liked her job as a graphic designer well enough, but it wasn’t fulfilling in the way she craved.

As she perused the church bulletin, an announcement caught her eye. A local pregnancy aid center was looking for volunteers, and Maryanne was compelled to answer the call.

She visited the center and liked it, but had no intension of becoming a counselor. Maryanne was a staunch introvert with a rigid personality. She tended to keep others at arm’s length. She wasn’t particularly social, had few friends, and wasn’t bothered by her lackluster love life. If she was going to volunteer, then she preferred to stay out of the public eye. Maybe she could help with design work, or man the phone.

At the center, Maryanne became close with another woman her age, who was more outgoing than Maryanne, and also more devout. She worked in New York City’s fashion industry, and spent her time on the subway praying the Rosary and reading the Bible.

She invited Maryanne to her Charismatic Renewal prayer group. Maryanne had no interest at all in these boisterous, revival-style meetings, and politely made her excuses. But her friend issued regular invitations, until one day Maryanne broke down and agreed.

The meeting wasn’t as bad as Maryanne expected – it was worse. People were speaking in tongues and waiving their hands in the air. The musicians played catchy, contemporary tunes. “I kept expecting Charles Manson to come out of the closet,” Maryanne said. The worst part came after the prayer service. Strangers kept trying to hug her. “I just wanted to get the hell out.”

When her friend called the next day to invite her to the next prayer meeting, Maryanne didn’t know what to say. It wasn’t her scene, but Maryanne valued their friendship, and had no other plans on Thursday, so she agreed to go.

Maryanne went the next week, and the week after. And soon she started enjoying the meetings as much as her friend. Once she got past the initial culture shock, she appreciated how warm and welcoming the people in the prayer group were. Soon, the habitually aloof Maryanne was part of a tight-knit group of women who met regularly for prayer and fellowship. Maryanne noted that, “I felt unconditional love, and I didn’t always feel that in my own family. They showed me what it meant to be emotionally intimate with female friends, and the Lord.”

Due to the group’s influence, Maryanne agreed to sign up for an eight-week seminar on Catholic theology. The subject held no particular interest for Maryanne, but she wanted to keep an open mind.

During the event, Maryanne was filled with a mystical presence. Her sins and shortcomings were swept away, and she was left with only God’s grace. The theology she was learning – about the value of life, and the importance of sexual purity – suddenly seemed vivid and relevant. Maybe Church Laws weren’t just drivel issued by a committee and intended to keep people from having fun. Maybe they came from a place of faith and ineffable joy.

Maryanne described the event as a conversion experience, and afterwards, she started going to Mass each morning before work. When she told her parents about her newfound faith, “My father looked at me like I said I was going to become a prostitute, and start hanging around on the street corner.”

Her participation in the prayer group, and her religious experience primed Maryanne to hear the whispered call to the sisterhood. She realized that, “The call to the priesthood or religious life isn’t bred in a vacuum. Some people are called, but they never learn how to hear it.”

When Maryanne told her friends about her call to religious life, she realized she was the last to know. One of her friends looked at her askance, and said, “Well, it’s about time!”

Which Convent is the Right Convent?

Even though Maryanne knew she was destined to join a religious order, she still had to decide which one. In some ways, applying to a religious order was like applying to college. Maryanne drew up a list of options, researched them, and visited several communities to see where she felt most at home.

From the beginning, she was attracted to a New Jersey community about ten miles from Philadelphia. The order was founded in Italy, many of the leaders were Italian, and the sisters were encouraged to learn the Italian language. For Maryanne, the order felt like an extension of her family. Several sisters were also involved in the Charismatic Renewal movement, and they encouraged Maryanne’s participation.

Most importantly, the sisters were down-to-earth and real. This wasn’t an order where the sisters seemed likely to float away in an ethereal mist. “I felt most at home with them,” Maryanne said. “Not that I didn’t have to change – I’d have to grow and get better – but the core of who I was could go there and stay the same.”

The only deterrent was the sisters’ primary mission of education. Maryanne was no more keen to be a teacher than a counselor. In one of her first conversations with the convent leaders, Maryanne made her reservations known. The sisters assured her they would find a suitable option. One of the sisters worked as a nurse, so being a teacher wasn’t a strict requirement. Satisfied, Maryanne began the long and involved process of becoming a sister.

Picking up the Habit

If Maryanne wanted to join the convent, she had to pass through five phases. First, she would spend a year visiting the convent for one weekend a month and getting to know the sisters. During this time, she was called an “aspirant.” She would maintain a separate residence, and would not be considered a member of the order.

At the end of the year, Maryanne would have to complete a battery of tests before she could be admitted as a postulant. She would write a mini autobiography for the sisters’ perusal, fill out a sixteen-page questionnaire, and complete psychological and physical evaluations. The sisters even drove out to Maryanne’s childhood home to meet with her parents.

As a postulant, she would spend one to two years in the convent, getting acclimated to the sisters’ schedule and work. She would also be expected to spend a great deal of time in prayer, asking God whether he really was calling her to a life of religious devotion. And if so, did he want her here?

At the end of her postulancy, she would write a letter petitioning to become a novice. Her novitiate would last another two years, and would come with further restrictions. She would not be allowed to leave the convent at all, and her family would only be allowed to visit every six to eight weeks.

At the end of her novitiate, she would write another letter requesting to take temporary vows. Once these vows were made, she would be called a junior sister, and would be fully engaged in either studying, or working through the convent. Temporary vows had to be renewed annually for at least five, and possibly up to nine years.

The last stage of a sister’s progression began when she took her final vows. Final vows were considered a lifelong commitment. After this step, Maryanne would be a senior sister.

Even as a senior sister, Maryanne would never technically become a nun. Her chosen order was an apostolic one, meaning the sisters left the convent and served the wider community. Actual nuns are expected to stay within the walls of their convent.

A Nagging Pain

There was one issue that nagged at Maryanne, but it was physical, not spiritual. In 1998, when she was an aspirant, she started feeling odd sensations in her pelvis and abdomen. She would get terrible cramps, which became atrocious during her period. She felt fatigued, had occasional back pain, and a general sense of malaise.

Her gynecologist diagnosed a yeast infection, but the prescribed medications had no effect. Urologists, neurologists, and gastroenterologists were all flummoxed.

In a perfect world, Maryanne would get her health under control before she moved into the convent. That way, she could devote her best energy to prayer and study. But her first doctors’ visits revealed nothing but uncertainty, and no one could say when, or if, she would get better.

She asked the sisters for guidance, and they encouraged her to listen to the Lord. If he was calling her to join the order, then her physical pain need not be an impediment. Maryanne heeded their advice, and in May of 1999, she entered the convent as a postulant.

But her pain remained a constant nuisance. Maryanne asked leave to visit doctor after doctor, but no one could name the thing that plagued her.

What in Hell Is This, Lord?

In 2001, about ten months into her novitiate, Maryanne was spending a solitary hour praying in the chapel, when she felt her pain shift. An intense burning filled her vagina, pelvis, and abdomen, and waves of numbness passed through her butt and thighs. She had the disturbing sensation that a foreign object was shoved up her rectum.

“What in Hell is this, Lord?” Maryanne prayed. “Where did it come from? Why do I have it?”

The sensations were so intense they took her breath away. She wracked her brain for a cause. The week before, she had helped move some of the order’s furniture into another building. She was carrying one end of a table, when she slipped and landed flat on her tailbone. She hadn’t noticed an unusual degree of pain at the time, but maybe she had injured herself without knowing it?

From that point on, the nature of Maryanne’s pelvic pain changed. It was no longer a nuisance, but a crippling, unendurable torment.

Sometimes, she would have a few hours of comfort after rising in the morning. But sitting down – especially if she’d just finished some physically demanding chore, like mowing the lawn – inevitably caused her pain to flare up again. Standing would bring some relief, but once the pain set in, it would last the rest of the day.

It might have been tolerable if Maryanne could think about something else for a while. But the convent had stripped away all distractions from prayer or duty. Novices had strict limits on TV and telephone use, and weren’t allowed to wander into the outside world alone. With so much quiet and stillness, Maryanne couldn’t help but fixate on her pain.

She couldn’t help but talk about it, either. The lack of entertainment also meant a lack of conversation topics, and Maryanne couldn’t keep quiet about a subject that occupied so much of her thoughts. Plus, Maryanne had to ask permission, and figure out transportation for each medical appointment. Even if she was inclined to be stoic, Maryanne couldn’t avoid bringing it up.

Some sisters reacted with kindness and compassion, but others wondered if the problem was Maryanne’s attitude. Whispers began to circulate. Sisters would ask why Maryanne didn’t smile, why she didn’t laugh. Admittedly, Maryanne’s disposition did nothing to improve the situation. She admits that, “I’ve never been a skippy, happy, glass-half-full kind of person.”

Like many people with chronic pain, Maryanne had good days and bad days. But the sisters’ schedule wasn’t open to negotiation, and there was little leeway available for sisters who couldn’t manage their daily duties. Whether it was a good day or a bad day, Maryanne was still expected to join the others at chapel at seven a.m., and then work, study, do chores, cook, clean, and pray at the appointed hours.

Too Much Therapy, and Too Little Relief

In the early years of the new millennium, Maryanne continued her fruitless scavenger hunt through the medical system. An orthopedist thought her pain stemmed from an injured facet joint in her spine, but the injection he recommended did nothing to help. Neither did her back surgery, or the implanted spinal cord stimulator.

A urologist thought she had interstitial cystitis, and ordered her to eliminate all acidic foods from her diet. Maryanne stayed away from pickles and orange juice, and popped the pills he gave her, until a diagnostic procedure showed she didn’t have the condition.

A neurologist refused to make any diagnosis at all, but suggested Maryanne focus on learning to manage the pain. He referred her to a pain clinic where, presumably, she would realize that her pain didn’t exist outside her head, and stop feeling it.

Meanwhile, Maryanne felt like the pain was dissolving her insides with a constant drip of acid. The burning sensation often radiated above her belly button, or into her back and legs. It superseded any pain she had ever experienced, or had ever imagined.

In 2005, a proctologist referred Maryanne to a physical therapist who specialized in pelvic floor massage. Maryanne endured an excruciating round of vaginal and anal massage, and afterwards resolved never to let a physical therapist do anything that involved removing her underwear.

When Maryanne called to cancel her next appointment, the physical therapist suggested she might have a condition called pudendal neuralgia. Maryanne had never heard the name before, but when the physical therapist explained what it was, Maryanne had to admit it was possible. When she got off the phone, Maryanne started Googling, and found testimonies from other women diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia. She started to cry. She had finally found others who understood her pain.

Maryanne would continue to see the physical therapist for the next two years. At the therapist’s suggestion, she also made regular visits to Philadelphia’s Pelvic and Sexual Health Institute.

The pain clinic was a refreshing change, if only because the staff understood pudendal neuralgia and could sympathize. In the spring of 2006, Maryanne underwent her first round of Botox injections.

The vaginal injection wasn’t terribly fun, and at first, it seemed to have been in vain. But after a few days, Maryanne noticed a definite reduction in pain, and by mid-June, she felt better than she had in years. For five months, Maryanne felt almost normal, and attended to her duties with renewed vigor. But the effects gradually wore off, and by Halloween, she had returned to her old normal.

A second round of shots failed to have the same effect. Maryanne couldn’t hide her disappointment. She had finally found an effective way to manage her pain, only to have it snatched out of reach.

The Last Chance to Stay or Go

By 2007, Maryanne had spent five years in temporary vows, and had to make a serious decision about her future. She could take her final vows, extend her temporary vows, or leave the order altogether.

It was a tough choice. Maryanne’s commitment to God and the sisters hadn’t waned and, despite the pain, Maryanne was happier at the convent than she had ever expected to be.

But at the same time, she was physically and emotionally exhausted, and didn’t know how much longer she could continue down the same path.

Maryanne loved her sisters, but communication among the organization’s leaders was bad and getting worse. Looking back, Maryanne saw a string of broken promises and a lack of concern for her well-being. When she joined, the sisters had promised she wouldn’t have to teach, but they stuck her in a second-grade classroom until Maryanne raised hell with the Mother Superior. “I sucked as a teacher,” she said. “I didn’t like it, and the kids knew I didn’t like it. I said, ‘don’t put me back in a classroom.’”

After that, Maryanne was transferred, and started spending one-on-one time with special needs students while she pursued a master’s degree in pastoral theology. That assignment was more to her liking, but the combination of full-time work, school, chores, and prayer, was too much to handle in poor health. She craved a respite, but the order’s leaders never seemed to get it.

Maryanne spent the two weeks leading up to her decision deadline searching for guidance anywhere and everywhere. She spoke to her priest, her counselor, and her physical therapist. She also prayed fervently, until one day she heard an answer. “Enough,” she heard Jesus’s voice in her heart. “It’s more important for you to leave, and take care of yourself, than to take final vows.”

And so, Maryanne met with the Mother Superior and explained her decision. She would not be taking her final vows. Instead, she planned to return to the secular world and…well, she hadn’t figured that part out yet.

The Mother Superior didn’t accept her answer without protest. “You’re making a mistake,” she told Maryanne. “You’re letting your pain get the best of you.” For two weeks, she kept after Maryanne, trying to convince her to change her mind.

Maryanne had waivered in her convictions before, but the sisters always persuaded her to stick around. The Mother Superior figured it would be the same this time around. But Maryanne held fast to her decision. She was sick of being second-guessed and ignored. She was sick of living in a sorority that couldn’t make space for her pain.

Life on the Outside

Although Maryanne was confident that she had made the right decision when she left the convent, the transition to secular life was disorienting. Outside of the order, she had no job, no car, no clothes, and no health insurance. The only money she had was the pittance she had brought with when she joined the order, and a small amount given to her from the convent.

But Maryanne turned to God, and this time, he answered her prayers. She moved in with her parents, which meant she saved on rent, and her distant family members and old friends sent clothes and cash.

Finding work was her top priority. Maryanne had no intention of picking up her career as a graphic designer. She’d spent eight years out of the industry. Besides, it was 2007, and she didn’t know how to use Photoshop.

But then she saw an ad in the local newspaper for a religious education director at a Catholic church an hour north. She sent one resume, attended one interview, and had a job within a month.

The priest and parish administrator took an instant liking to Maryanne, and they became fast friends. When the priest learned she didn’t have a car, he gave her some money to buy one. He also waived the usual three-month waiting period for health insurance, and added her to the policy, effective immediately.

Maryanne loved the job. She loved the kids, and she loved their families. She loved the priest, and she loved her coworkers. She quickly made friends with three other single women at the parish, who would sometimes let her stay overnight if she didn’t fancy making the two-hour round-trip home.

But although she loved many parts of her new life, Maryanne grieved for the life and friends she had left behind at the convent. “I was beyond devastated,” she said. “I nearly had a nervous breakdown. I missed the sisters like crazy. Those first two years were really, really hard. I wasn’t wearing the habit anymore, but I still felt like Sister Maryanne.”

At least she now had time to look after her own health. She also had access to something she hadn’t been allowed for eight years – mindless entertainment. If Maryanne’s pain flared up, she could flip on the TV, or pick up a novel, or piece together a jigsaw puzzle. It was a welcome change from the convent, where the only pastime encouraged was prayer.

Life Can Overwhelm You Anywhere

Maryanne stayed at her job for five years. It was a lot of responsibility, and a lot of stress, but the love and support she found in the community helped her carry on.

In 2012, Maryanne suffered a personal tragedy when her father died of kidney cancer. Maryanne decided to take a job closer to home, so she would be able to spend more time helping her mother. Her new job involved the same kind of work, but was only a twenty-minute drive away.

Maryanne had started seeing a wonderful doctor in New Brunswick, but there were very few treatments available to treat her condition. Maryanne’s health was slipping. She was losing control of her bladder and bowels, and her pain got worse. She gained weight, partly as a side effect of the Lyrica she was taking to control the nerve pain.

After two painful years at her new job, she retired in the summer of 2013. She filed for disability, but her claim wouldn’t be approved until 2015.

But being on disability didn’t mean Maryanne was free from work. She never had much of an opportunity to build up her savings, and the disability benefits she received weren’t enough to cover her expenses. To help fill the gap, Maryanne got a job doing administrative work at a law firm for fifteen hours a week. The arrangement lasted for three years, until Maryanne was laid off in the economic turmoil in the wake of COVID-19.

Today, Maryanne works part time taking care of an elderly woman in her neighborhood. She lives with her 81-year-old mother, and both women benefit from the other’s company.

Cliché as it is, Maryanne gets by one day at a time. She tries not to imagine the future in years; there is too much pain waiting for her. She is still on Lyrica, and gets regular injections to help with the pain.

Where Is Pain in Faith?

As a sister, Maryanne spent several hours a day in prayer, and she pestered the Lord with questions and requests about her pain. She asked the Lord to heal her, and she went to healing masses where other people prayed over her. And yet, God said nary a word in reply.

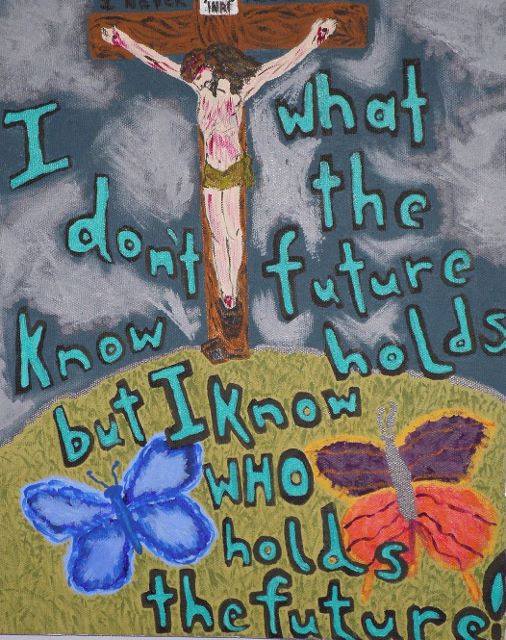

In 2005, while stationed at a smaller house a few miles south of the main convent, Maryanne had a heart-to-heart talk with the Mother Superior. The older woman said, “Has it ever occurred to you that this is God’s will for you? For whatever reason, he’s asking you to carry this cross.”

Maryanne didn’t want to hear it. She threw a tantrum, in which she cried, and screamed at the Mother Superior.

But while she fought hard against the Mother Superior’s words, eventually they started to sink in. “Little by little, I started to accept that, for whatever reason, this was the cross I had to bear,” Maryanne said. “I still don’t know why that is. Why did God bring me to the convent for it? Why did I go, but not take final vows? It seems like a lot of wasted time.”

It wasn’t until years after she left the convent that Maryanne felt a real shift in attitude. “I abandoned the whole situation to the Lord. I didn’t stop praying that I’d find treatments that would help, but I stopped praying to be completely healed. I started praying for the grace to accept things as they were going to be. Whether healing comes, or doesn’t come, I want to learn how to live with this.”

One question she didn’t ask was, “Why me?” For Maryanne, the better question was, “Why not me?” When she had a bad pain day, Maryanne offered her pain up to the Lord in the hopes of relieving another person’s suffering.

Maryanne doesn’t see her pain as a blessing in disguise. But in a strange way, it’s led to a closer relationship with God. “If it wasn’t for my chronic illness, I wouldn’t have the relationship I have with the Lord now. If it wasn’t for faith, I would be either physically dead, or emotionally and psychologically dead. But I believe all of what the church teaches, that suffering gives life meaning, that suffering has redemptive powers. It is what it is. It’s God’s grace.”

She’s also finishing up her memoir. Maryanne harbors no illusions about becoming a famous author, but she hopes that by getting her story out there, it will find its way into the hands of someone who needs it. “It’s a powerful story,” she said. “It’s really God’s story to tell, through me. It’s about God’s love, and how his grace got me through.”

Beautiful story, thank you.

What a beautiful story! Thank you for sharing. I learned so much more about a wonderful friend! You were a great Director of Religious Education and loved by many at our church!

Maryanne, I came across this tonight. Our lives are very similar. I live at the South Jersey Shore. I moved here from W Deptford 4 yrs ago. I got PN the beginning of 1999. I wasn’t diagnosed for yrs. I went to 39 doctors before I was diagnosed. I also went to the Pelvic Pain and Sexual Health Institute at Hahnemann Hospital, Philadelphia.

I am married 51 yrs and have 2 daughter and five grands. I am Catholic. What Order were you in the Convent? I belong to 4 PN sites, one is in the UK. Pudendal Neuralgia Hope site was my first. I would live to chat with you. My phone number is 856-904-3477. If you want to get in touch please send a text first because I don’t answer phone calls unless you are a contact.

I have become closer to God, very close the last couple years because of my PN. I have come to realize that PN is part of his plan for my life. I still would absolutely want it to go away or that there would be a cure, but I know it will not happen in my lifetime.

Hope you reach out to me in the near future.

Thank you for your story ….

I also have pudential nerve pain increased by a nerve surgeon through his surgrey.I live in constant pain.Your story touched me because I never thought about never getting rid of it.Mine is so complicated.It even affected my feet in neurapathy.Maybe this is my cross to bare also.I hope the best for all sufferers.