I can certainly understand how a bad case of sciatica could cause a person to spiral into depression. But until recently, it never occurred to me that antidepressants could be prescribed as painkillers. But a recently published review in BMJ pointed out how widespread the practice is – and how effective antidepressants are at treating sciatica and back pain. (Spoiler: Not very.)

The authors of the study synthesized data from 33 separate studies to ascertain how well different classes of antidepressants treated three common health concerns: back pain, sciatica, and knee osteoarthritis. (I’m going to focus on the first two.)

They considered two measures: 1) How antidepressants influenced pain scores, and 2) How antidepressants influenced disability scores. Both were measured on a scale of 0–100.

Antidepressants: The New Aspirin

When my sciatica first became unmanageable back in 2017, I made regular treks to doctors’ offices. The doctors would inform me of my pharmaceutical options in such a way that I would inevitably pick their favorite pill. Yet, none of them ever mentioned antidepressants. So I was surprised to learn just how often antidepressants are prescribed for chronic pain relief.

The authors of the study (based in Australia) pointed out that 7.2 million Brits were prescribed antidepressants, while 5.6 million were prescribed opioids in a single year (the data covered the final three quarters of 2017, and the first quarter of 2018). In the US, more than a quarter of people with chronic low back pain are given antidepressants.

And no wonder – medical societies explicitly endorse their use for these purposes. A separate review of clinical practice guidelines found that 80% (8 out of 10) of the guidelines recommended antidepressants to treat low back pain.

For the record, 87% of the guidelines (13 out of 15) considered recommended using opioids, at least in some circumstances.

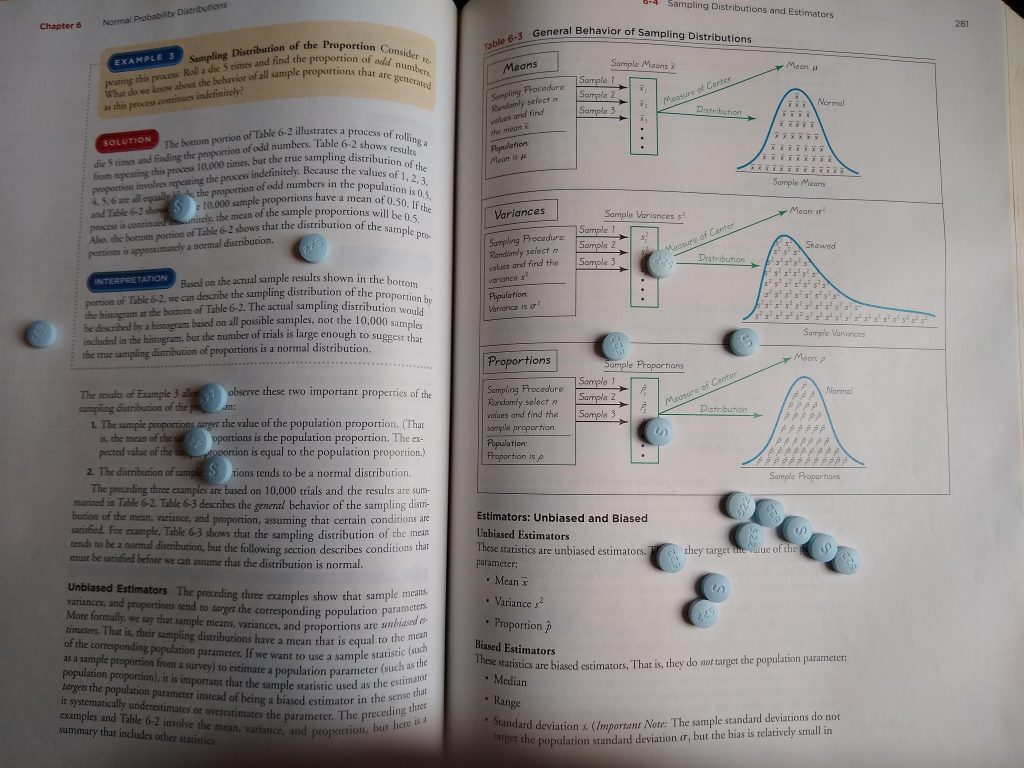

A Refresher on Statistics

In case you spent your high school math classes staring at the back of your crush’s head, rather than focusing on the chalkboard, here’s a quick review of the statistics concepts you need to interpret these study results.

The researchers reported the mean (or average) difference in pain and disability levels on a 100-point scale. For example, let’s say 100 patients suffered from back pain at the start of a study. The average pain score they reported at the beginning of the study was 85. Then, after taking some pain medicine, their average pain score dropped to 60. In this case, the mean difference would be -25 (because 60 – 85 = -25).

The researchers also listed the 95% confidence interval range. This means that if a person meeting the criteria was selected from the population at large, there is a 95% chance that their pain reduction would be in the same range.

Using the example above, let’s say that the 95% confidence interval listed was -35 to -15. This means that if we selected a random person with back pain and gave them the medication, there is a 95% chance that they would report a reduction in pain somewhere between -35 and -15 points.

You may notice that the range is ±10 points from our mean of -25. The mean will always be at the exact center of the confidence interval.

Because this study is looking at pain relief, big negative numbers are good. -35 means greater pain relief than -15. A positive number is bad, because it means pain levels actually increased.

The authors considered the smallest clinically meaningful difference to be -10.

Types of Antidepressants

The authors of this study looked at six different classes of antidepressant drugs. Here’s a primer, in case you’re not a pharmacology expert.

- Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): This class of drugs blocks the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, which increases the levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain. They are also sometimes prescribed for treating anxiety or bipolar. SNRIs include:

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- Venlafaxine (Effexor XR)

- Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq)

- Levomilnacipran (Fetzima)

- Milnacipran (Savella)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): This class of drugs blocks the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, which increases the levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain. They also work on other neurotransmitter receptors, though the specifics vary by drug. They tend to have more side effects than SSRIs, so they usually aren’t the first choice for depression. TCAs include:

- Amitriptyline

- Amoxapine (Asendin)

- Doxepin (Sinequan)

- Desipramine (Norpramin)

- Nortriptyline (Pamelor)

- Protriptyline (Vivactil)

- Imipramine (Tofranil)

- Trimipramine (Surmontil)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): This class of drugs blocks the reuptake of serotonin, which increases the levels of serotonin in the brain. They are also sometimes prescribed for treating anxiety. SSRIs include:

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- Vilazodone (Viibryd)

- Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): This class of drugs blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, which increases the levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain. They are also used to treat bipolar depression and ADHD. The only NDRI that is commonly used to treat depression in the US is bupropion (Wellbutrin).

- Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs): This class of drugs blocks the reuptake of serotonin, which increases the levels of serotonin in the brain. They are also sometimes prescribed to treat anxiety and insomnia. Examples of SARIs include:

- Trazodone (Oleptro, Desyrel)

- Nefazodone (Serzone)

- Tetracyclic antidepressants: These are similar to tricyclic antidepressants, but have a slightly different chemical structure. They block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, which increases the levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain. Examples of tetracyclic antidepressants include:

- Maprotiline (Ludiomil)

- Mirtazapine (Remeron)

- Amoxapine (Asendin)

Antidepressants and Back Pain

A majority of the studies included in the review (19 out of 33) included data on back pain and antidepressant use. Since the evidence for back pain is strongest, it’s a good place to start.

The results, in all categories, were rather lackluster. For pain measures, SNRIs, SSRIs, TCAs, NORIs, SARIs, and tetracyclic antidepressants all had negligible effects for all measured time frames.

TCAs had the noteworthy effects. At least, if you’re willing to wait.

- ≤2 weeks:

- Mean difference -.86

- 95% confidence interval: -5.40 to 3.68

- 3–13 weeks:

- Mean difference: -9.96

- 95% confidence interval: -21.50 to 1.58

- 3–12 months:

- Mean difference: -7.81

- 95% confidence interval: -15.63 to 0.01

Again, these numbers are measured on a 100-point scale.

There are a few caveats to keep in mind when interpreting these results. The 3–13 week data was based on 7 separate studies with 591 total participants. That’s a decent (though not exceptional) number. However, the researchers noted that there were several methodological problems with the included studies, so they rated their certainty in the evidence as very low.

The numbers in the 3–12 month time frame were based on a single study.

When it came to disability measures, there was no evidence either way for NORIs and tetracyclic antidepressants. The numbers for SNRIs, SSRIs, TCAs, and SARIs were roughly similar to those for pain relief. Meaning, the effects were so small they were unlikely to make a difference to patients.

Again, the effects were largest for TCAs, although again, the authors expressed concern about the quality of the data.

- ≤2 weeks: No data

- 3–13 weeks:

- Mean difference: 12.94

- 95% confidence interval: -26.47 to 0.59

- 3–12 months:

- Mean difference: -4.30

- 95% confidence interval: -10.49 to 1.89

Antidepressants and Sciatica

There was less data (6 studies out of 33) available on the use of antidepressants for sciatica compared to back pain. Only two classes of antidepressants could be evaluated: SNRIs and TCAs.

The authors noted that, “Caution is needed in interpreting our findings for sciatica. All sciatica trials were small, had imprecise estimates, and were at high risk of bias, which reduced the certainty of evidence to low and very low. This level of uncertainty indicates that the true estimate of effect of TCAs and SNRIs for sciatica is likely to be substantially different from what we estimate in our review.”

The results are still interesting, and possibly useful. They are not, however, conclusive.

At first glance, the effects of antidepressants on sciatica appear to be larger. For SNRIs, the average pain reduction at under 2 weeks was -18.60, with a 95% confidence interval of -31.87 to -5.33. However, those numbers come from a single study that involved only 50 participants, who were split between treatment and placebo groups.

At 3–13 weeks, the mean difference was -17.50, with a 95% confidence interval of -42.90 to 7.89, which is quite a spread. These results are based on 3 studies. However, there were still only 96 patients included.

TCAs appeared to offer a moderate pain relief benefit during all time frames.

- ≤2 weeks:

- Mean difference -7.55

- 95% confidence interval: -18.25 to 3.15

- 3–13 weeks:

- Mean difference: -15.95

- 95% confidence interval: -31.52 to -.39

- 3–12 months:

- Mean difference: -27.00

- 95% confidence interval: -36.11 to -17.89

The results were less impressive when it came to disability measures, but again, TCAs did seem to offer some benefit.

- ≤2 weeks:

- Mean difference: -5.00

- 95% confidence interval: -12.23 to 2.23

- 3–13 weeks:

- Mean difference: -8.42

- 95% confidence interval: -18.18 to 1.35

- 3–12 months:

- Mean difference: -20.00

- 95% confidence interval: -27.74 to -12.26

Antidepressants for Knee Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is not the main focus of this blog, so I won’t go into detail here. Suffice it to say that the results were not super compelling here either. There was some evidence that SNRIs are mildly helpful at reducing pain in the 3–13 week time frame. The mean difference was -9.72, and the 95% confidence interval was -12.75 to -6.69.

When it came to disability and osteoarthritis, the benefits of antidepressants were small, and unlikely to be meaningful to patients.

Takeaways

Some types of antidepressants might have a limited impact on pain ratings, sometimes. Although the data for sciatica is not as strong as could be hoped, it appears that SNRIs and TCAs may be somewhat effective.

That, at least, is a scientist’s perspective. As a patient, I want to be sure that any drug I use to manage sciatica makes a significant difference. I certainly don’t want to deal with the hassle, expense, and side effects of medications unless they make my life significantly better. And antidepressants do have their fair share of side effects.

Personally, this review doesn’t encourage me to jump on the antidepressant bandwagon. There are plenty of cheap and non-habit-forming options that make just as great a difference. For me, these include walking and drinking enough water.

And when I need to deal with my sciatica-related grumpiness, there’s nothing like a good nap.

One thought on “Can Antidepressants Treat Sciatica?”