You would never know it, to hear my mangled sentences and unpardonable accent, but I took four years of Spanish in high school. While I can’t remember the difference between the past perfect and the pluperfect, I do remember who Frida Kahlo is.

Why the heck is she famous? I wondered, as I flipped through reproduced paintings of watermelons, and Kahlo posing with monkeys. My textbook noted Kahlo was known for her self-portraits, which was strange, because she hadn’t even bothered to edit out her unibrow.

Beyond her odd style choices, I wondered how any artist could became famous for specializing in such an awfully narcissistic genre. Couldn’t she find something more interesting to paint? Something besides watermelons?

Two Reminders of Frida

After passing that Spanish test, I had no further reason to care about Kahlo, and so I dismissed her as an example of the art world’s commitment to being incomprehensible. I might never have thought of her again, except that in the last year, two incidents served to bring Kahlo back to the front of my mind.

First, I read Leslie Jamison’s essay, “Pain Tours (II),” which begins:

“Frida Kahlo wore plaster corsets for most of her life because her spine was too weak to support itself. She painted them, naturally, covering them with pasted scraps of fabric and drawings of tigers, monkeys, plumed birds, a blood-red hammer and sickle, streetcars like the one whose handrail rammed through her body when she was eighteen years old.”

Ah, yes. I remembered reading something about a streetcar accident in my high school textbook. Funny, how I hadn’t thought much about it at the time. But as a thirty-three-year-old woman with my own spine problems, this accident seemed significant in a way it hadn’t before. I realized that Kahlo must have endured decades of excruciating pain. Suddenly, her accomplishments seemed more remarkable.

Second, I watched the 2002 movie Frida, with Salma Hayek playing the title character. The movie was beautiful and compelling although, to be fair, the facts of Kahlo’s life don’t require much in the way of artistic license to become great drama. I was spellbound.

In Kahlo’s Paintings, Pain is Forever Urgent

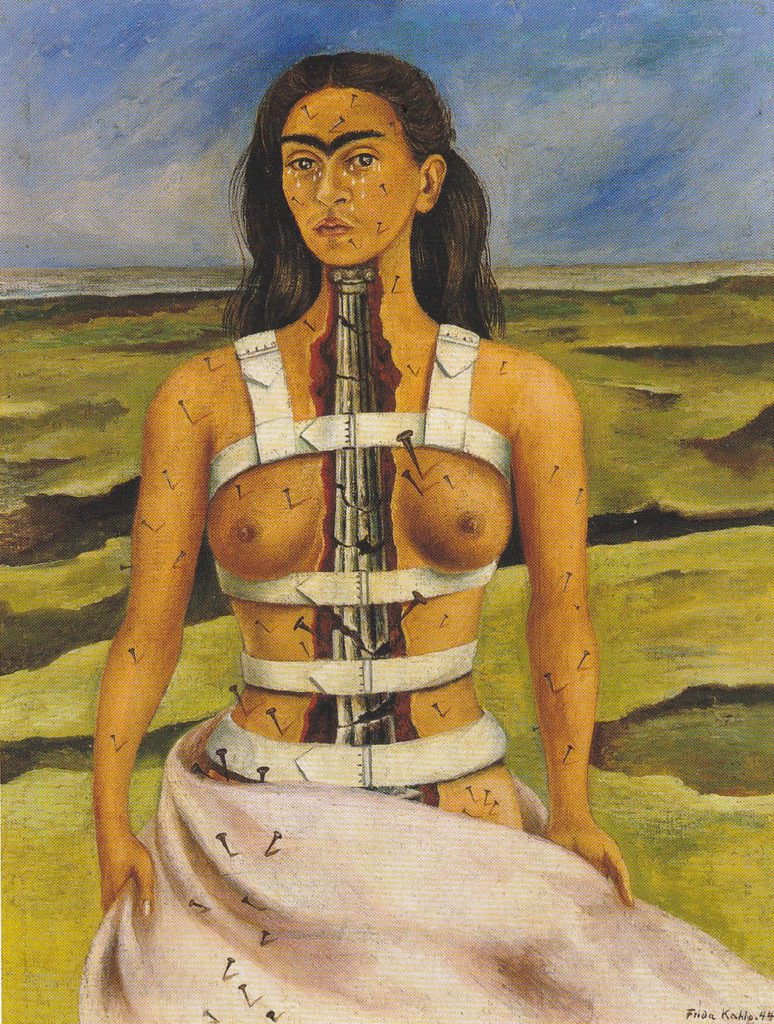

The movie (and my subsequent Googling) also introduced me to works of art that were too horrifying (or “triggering,” in today’s parlance) for a high school textbook. These paintings portrayed Kahlo’s pain with an immediate intensity, even though they were the product of another time and place.

There was Kahlo’s head on a deer, her body pierced with arrows. There was Kahlo, armless, with a rod through her chest and an enlarged heart bleeding into the ground. There were two Kahlos with blood pouring from their exposed hearts.

Photo courtesy of Jens Cederskjold via Flickr.

Many of Kahlo’s paintings include details lifted from medical textbooks. The clinical images are jarring when placed into such intensely emotional contexts. Kahlo always had an interest in science and medicine, and before her streetcar accident, she considered becoming a doctor. Later, she would get plenty of medical experience as a patient.

Some of Kahlo’s best-known works were done in response to medical emergencies. After a futile spinal fusion surgery, Kahlo painted Tree of Hope. It shows two versions of Kahlo. One figure is reclining on a hospital gurney, wrapped in a white sheet that splits to reveal the bloody incisions in her back.

The second figure is sitting upright on a chair, wearing the Kahlo’s signature Tihuana style, and is holding a back brace. She also clutches a small flag, upon which are written Spanish lyrics which translate to, “Tree of hope, remain strong.” The cracked and parched desert stretches out behind the figures.

Henry Ford Hospital, which was painted after a devastating miscarriage in Detroit, again shows Kahlo reclining on a gurney. She clutches a handful of red lines, which look like balloon strings but also like viscera, which connect her abdomen to array of images: pelvic bones, a snail, an orchid, a medical model of the female torso, an unidentifiable machine, and a male fetus.

Kahlo painted The Broken Column, after another yet another spine surgery. It shows Kahlo topless, her torso encased in the straps of a medical corset. The skin in the center of her body has been peeled away, revealing the fractured remains of an ionic column. Nails pierce her skin; a particularly big one is stuck near her heart.

Kahlo suffered her share of pain and medical mishaps. Many other people do, too. Kahlo’s genius was in processing that pain, and creating a visual vocabulary which clearly vocalized it. Remarkably, she managed this visual eloquence even when tackling subjects (such as miscarriage) that had been rarely been depicted before.

Photo courtesy of Yuan Tian via Flickr.

Disability Intertwined with Identity

Kahlo’s health problems began when she was six years old, when a bout of polio left her bedridden for nine months, and left her with a permanently malformed right leg. When she was finally well enough to move around, she walked with a limp that earned her the nickname “Frida pata de palo” (“Frida peg-leg”). (Ankori 2013)

When she was eighteen, Kahlo was involved in a near-fatal accident when a streetcar crashed into the bus she was riding. Her right leg, already withered from polio, sustained eleven fractures, and her right foot was crushed. She broke her spine in three places, and her pelvis in another three. She broke her collarbone and two ribs, and dislocated her left shoulder. Perhaps most gruesome of all, an iron handrail impaled Kahlo through the abdomen, entering at her left hip, and exiting through her vagina.

This injury left Kahlo susceptible to gynecological problems, and she was never able to have children. In 1932, Kahlo, who was traveling in Detroit, suffered a miscarriage so severe she nearly bled to death.

During her life, Frida was subjected to countless medical tests and underwent more than 30 surgeries. She often relied on medical corsets, body casts, and, towards the end of her life, a prosthetic leg. She tried countless treatments, drugs, and therapies, but never found her miracle cure.

Is it any wonder, then, that Kahlo’s work reveals a preoccupation with death and suffering? In a drawing from her diary, she declares, “I am the DISINTEGRATION…” while a 1943 painting shows her Thinking of Death. Kahlo portrays death as her companion since birth. Her 1937 painting My Nurse and I shows an infant Kahlo suckling at the breast of a wet nurse wearing a pre-Colombian funeral mask.

Her right leg, always a source of pain, sustained numerous ulcers and infections, and ultimately became gangrened. In 1953, doctors amputated it below the knee. According to Kahlo’s nurse, the loss of her leg seemed to crush what was left of Kahlo’s spirit, and she died the following year, on July 13th. The official cause of death was a pulmonary embolism. Kahlo was 47 years old.

Photo courtesy of libby rosof via Flickr.

A Chronic Broken Heart

In addition to her physical suffering, Kahlo also sustained innumerable emotional wounds.

Even as a teenager, Kahlo was destined to love people who couldn’t love her back, at least not exclusively, and she felt the lack of affection keenly. In high school, she had an affair with a female gym teacher, who was simultaneously having affairs with two other girls. All three of the girls were aware of this arrangement, and Kahlo later admitted it inspired much jealousy.

At age 15, Kahlo started classes at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, where she fell in love with the charming Alejandro Gómez Arias. While they were dating, Gómez Arias was also in a relationship with a male classmate, Jesús Ríos Ibúñez y Valles. Again, everyone involved was aware of the tangled love triangle. Kahlo and Ríos Ibúñez y Valles would often talk about their shared lover, and offer each other advice.

Alejandro Gómez Arias was traveling on the bus with Kahlo during the fateful streetcar accident, although he escaped without injury. During Kahlo’s lengthy convalescence, he remained noticeably absent from her bedside. While she was still in the hospital, he sent a letter from Veracruz explaining his plans to travel to Europe.

Although they continued to exchange letters for some time, and Kahlo sent Gómez Arias an early self-portrait in which she styled herself as a modern Venus, their romantic relationship was effectively over, and Kahlo was left to ponder why she was so unlovable.

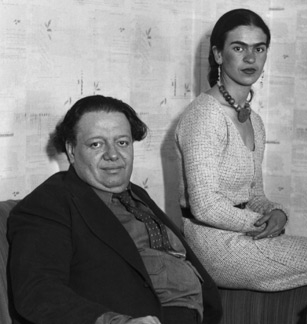

In 1928, three years after the accident, Kahlo began a relationship with the famed muralist Diego Rivera, whom she had known (and whose work she had admired) since the age of fifteen. The couple married the next year, when Kahlo was twenty-two, and Rivera was forty-three.

It was never a monogamous relationship. The period of their courtship was a time of particularly intense romantic activity for the notoriously girl-crazy Rivera.

Although Kahlo and Rivera both engaged in numerous affairs during their marriage, theirs was no evolved open marriage. Kahlo was often wounded by Rivera’s poorly-concealed affairs, and Rivera was often jealous of Kahlo’s male lovers.

A particularly painful episode happened when Rivera had an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister, Cristina. Around the same time, Kahlo suffered a third pregnancy loss, and needed surgery to remove several toes from her right foot. The double betrayal, which came at a time when Kahlo was particularly vulnerable, devastated her.

In 1939, Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship reached its low point, and the couple filed for divorce. During their brief separation, Kahlo tried and failed to achieve financial independence. But, remaining separated proved harder than either expected, and the couple remarried on December 8th, 1940. (Frida Kahlo Timeline n.d.)

When she felt wounded, Kahlo couldn’t find solace in fame and success. Although she was the subject of several news articles, photographs, and even a play, she never managed to support herself through her art. While she was alive, her most expensive painting sold for a mere $400. She remained financially dependent on Rivera until her death.

The Original Selfie Queen

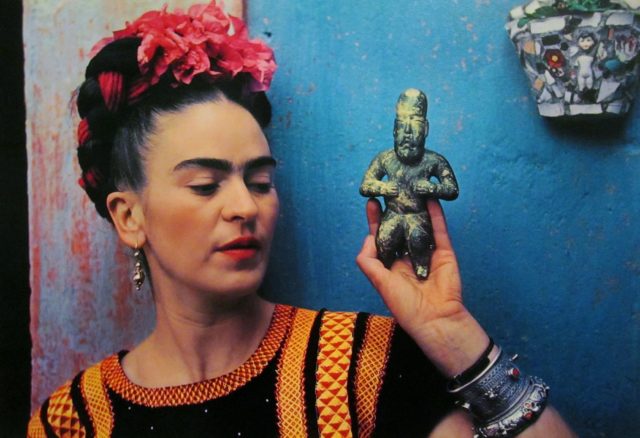

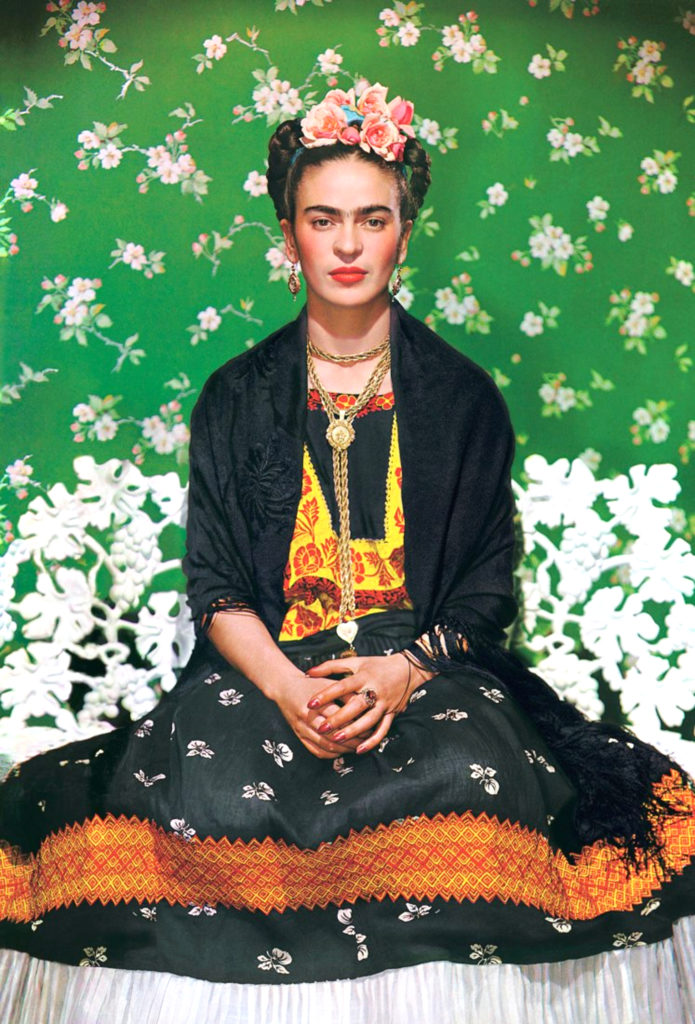

When I first learned about Kahlo, there was something about her that rubbed me the wrong way. Yes, I found her choice of subject narcissistic. I was also put off by what I perceived to be her overly self-conscious styling and dress. Her propensity for collecting, stringing, and – imagine! – even painting ancient Mayan jade beads seemed inexcusably selfish.

In addition to the aforementioned jade beads, Kahlo’s favorite accessories included a gold pendant of similar antiquity, and gold teeth set with diamonds. She was known for her extensive collection of jewelry. She was constantly giving and receiving necklaces, earrings, and especially rings. (Wilcox and Henestrosa 2018)

Kahlo was willing to experiment with gender roles, and in a few cases, she portrayed herself as a man. Close inspection of a Kahlo family photo from 1926 reveals that the moody young man on the left is actually Frida. Her 1940 painting Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair shows Kahlo wearing a man’s suit, while the floor around her is littered with locks of shorn hair.

But most of the time, Kahlo emphasized her feminine qualities, and downplayed those features which she considered masculine. She had a vast knowledge of art history, and she often evoked other paintings and styles to portray herself as the Madonna, Venus, La Llorona, and other quintessentially female subjects.

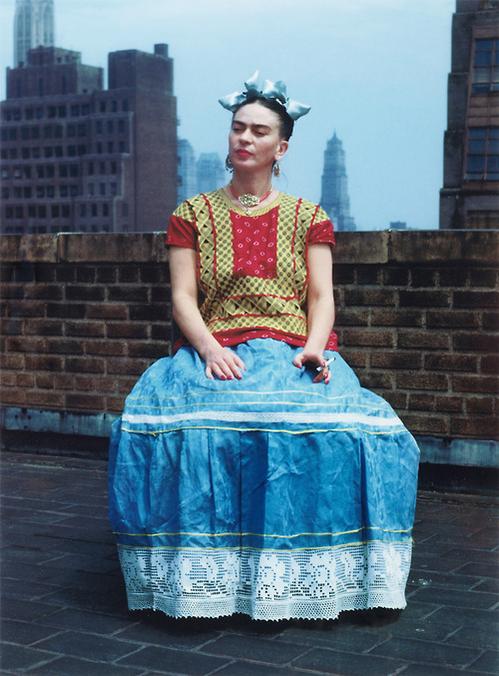

Kahlo adopted the Tehuana style of dress as her signature look. A typical outfit consisted of a floor-length skirt called an enagua, a geometric embroidered tunic called a huipil, and a long shawl called a rebozo. Kahlo also styled her hair into an elaborate arrangement of braids adorned with bright flowers.

Photo courtesy of Antonio Marín Segovia via Flickr.

Kahlo wasn’t the only Mexican luminary to admire the Tehuana style, and the native Zapotec people. Many intellectuals and revolutionaries were embracing their native Mexican heritage, and using it to construct a new national identity. The Zapotec women were renowned for their beauty, independence, and high spirits.

Given Kahlo’s own sensibilities, it’s easy to understand why she adopted the Tehuana style as her own. First, by donning this distinctly Mexican costume, Kahlo reflected her fierce pride in, and identification with, the Mexican people. Second, it allowed Kahlo to adopt into a model of femininity that fit her own personality. (She was never going to be an obedient, chaste Catholic mother.)

But, with Kahlo, there is always another layer of thought. Kahlo’s signature look was, at least partly, a calculated choice to draw attention away from her self-perceived weaknesses. The floor-length skirts served to cover her withered right leg, while her colorful blouses and hairstyles drew attention to her upper half. A pair of Kahlo’s boots show two heels of different heights; a practical way to mask the discrepancy in leg lengths.

Un-Judging Frida Kahlo

The more I looked into Kahlo’s photographs, paintings, and fashions, the less keen I was to assign labels like “narcissistic” and “self-obsessed.” Partly, this is because Kahlo’s complicated personality defies all such one-dimensional labels. It was also because I realized how foolish I was to judge a painter, and the daughter of a photographer, for being overly concerned about aesthetics.

But I also came to understand Kahlo as a profoundly wounded woman who nevertheless, did the best she could. If long skirts allowed her to stop worrying about her withered leg, then who was I to call her vain? And if her flashy rings and gold chains let her forget about the body cast she wore under her dress, then who was I to question her?

Even if Kahlo’s clothes, hair, and jewelry, were all a matter of public preening, could I really fault her? During her lifetime, she was overshadowed by a famous husband. Even articles about Kahlo often referred to her as Rivera’s wife, rather than using her own name. Was this her way of carving out a little space for herself? For being recognized as an individual distinct from her husband?

If I was inclined to raise an eyebrow at Kahlo’s tortured love life or numerous affairs, I started to question my judgment there, too. Was Kahlo really a shortsighted sensualist with poor taste in men? Or was she starved for an authentic love she thought herself unworthy of?

Were her affairs with icons like Leon Trotsky, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Nickolas Muray really about feeding her ego? Or was affection so necessary to Kahlo that she would pursue it, regardless of the risks?

I’m not sure I can answer these questions. I’m not sure I should try.

Perhaps it’s enough to know that the façade is not the building. That people are complicated. That strange, and even objectionable behavior might belie a deeper truth I can’t know. That maybe the best thing to do is to learn to look without judging.

Note: I relied heavily on Gannit Ankori’s book, Frida Kahlo, for the biographical details I used in this article.

Photo courtesy of RV1864 via Flickr.

References

- Ankori, Gannit. 2013. Frida Kahlo. London: Reaktion Books, Limited.

- n.d. Frida Kahlo Timeline. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.fridakahlo.org/frida-kahlo-chronology.jsp.

- Herrera, Hayden, Clancy Sigal, DIana Lake, Gregory Nava, and Anna Thomas. 2002. Frida. Directed by Julie Taymor. Produced by Mark Amin, Lindsay Flickinger, Brian Gibson, Mark Gill, Sarah Green, Nancy Hardin, Salma Hayek, et al. Performed by Salma Hayek, Alfred Molina and Geoffrey Rush.

- Jamison, Leslie. 2014. “Pain Tours (II).” In The Empathy Exams: Essays, by Leslie Jamison, 185–218. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press. https://www.graywolfpress.org/books/empathy-exams.

- Wilcox, Claire, and Circe Henestrosa. 2018. Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up. London: V&A Publishing. https://www.vam.ac.uk/shop/frida-kahlo-making-her-self-up-153329.html.