Health care providers love to ask questions that serve no apparent purpose. Why do they need to know, for example, what my marital status is? Would I get different meds as a single person? Is my occupation relevant when I have a sinus infection? And if I don’t feel safe at home, then what, realistically, is the nurse going to do?

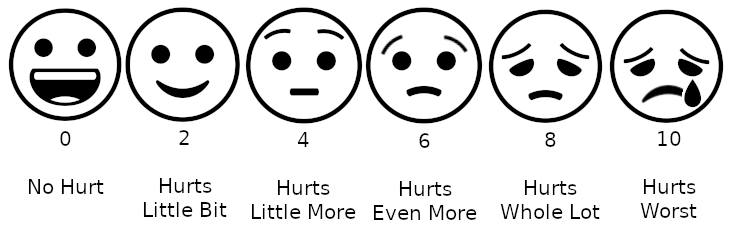

But the question I find most baffling is, “What is your pain level today?”

First, any numerical rating I can give seems to dodge around any information that is actually useful. And second, whatever number I give never seems to affect my treatment.

So why? Why even ask if the answer doesn’t matter? What is this question supposed to accomplish? Is there any way I can use it to game the system?

I set out to answer these questions, and quickly realized the answers were knotted up with a complicated tangle of history, ethics, and medical fashion. And by that, I mean, opioids.

The Old Question: To Medicate, or Not to Medicate?

Recent sources on pain ratings and their uses are cloaked in euphemisms and vagaries. For example, this FAQ from 2000 instructs physicians to give a perfectly useless answer to a sensible question:

Q. “Why are you asking me about my pain?”

A. We take pain very seriously and consider it a vital sign. You can expect to be asked about pain each time you see your primary doctor or nurse practitioner and when someone takes your other vital signs such as your temperature or blood pressure.

But as I traced pain management philosophies back through time, sources became increasingly clear about the link between patient-reported pain ratings and analgesics. The question, “What is your pain level?” was used to answer a more practical question, “Does this patient need more pain meds?” Specifically, “Does this patient need more opioids?”

The trade-off between pain relief and addiction is hardly new, and the pendulum has been swinging back and forth since at least the 1860s, when doctors believed that intravenous injections of morphine could cure opium addiction.

By the mid-twentieth century, the pendulum was swinging back in favor of opioid use. Practitioners began to wonder whether the resistance to prescriptions was causing more harm than good.

The 1973 article, “Undertreatment of Medical Inpatients with Narcotic Analgesics” is a particularly good example. In it, the authors argue that fears of opioid addiction are misplaced, that the actual risk of addiction for inpatients is low, and that undertreatment is the more serious concern.

Their anxieties were not entirely baseless. Some patients were being ignored or dismissed. They report, “[A] patient, causing disturbance because of severe pain in the stump of his amputated leg, was being treated with minimal and erratic doses of narcotics because the house staff thought he had an ‘addictive personality’ and therefore doubted the reality of the pain. Subsequent evacuation of a large abscess from the stump confirmed the fact that the patient had been undertreated. Again, we were called to see a patient in sickle-cell crisis because she was threatening suicide. It turned out that threatening suicide was her desperate attempt to get more medication for her severe pain.”

Tangent: I have a hard time controlling my outrage when doctors without psychological training make arbitrary decisions about which pain reports are valid, and which are not. I have no history of substance abuse or trauma, and no psychiatric diagnoses. But I’ve called doctors in desperation and begged for anything that might help. It would be too easy for doctors to write off my (very real) distress as drug-seeking behavior. They don’t know me, and they don’t know better.

Back on topic: I’m going to assume that the authors were motivated by compassion for patients, and a genuine desire to relieve suffering. But some of their assertions invite scrutiny.

For example, they estimated that after a ten-day course of opioids, a hospital inpatient had less than a 1% chance of becoming addicted. They went on to estimate that the same patient had greater than a 50% chance of experiencing withdrawal symptoms. So withdrawal symptoms are somehow…not indicative of addiction? Maybe views of addiction were different in the 1970s, but, really?

Pain as the 5th Vital Sign

By the 1990s, the undertreatment-is-the-real-problem theory was gaining critical mass. Contemporary critics pointed out that pain was invisible, and therefore ignored. As one prominent advocate noted, “pain relief has been nobody’s job.”

Influential thinkers at the NIH, American Pain Society, and other groups began pushing to destigmatize medication use and make pain more visible. They suggested sweeping changes, ranging from better tools for managing medications, better patient communication, and – most important for our purposes – mandatory tracking of pain levels and pain relief efforts.

In 1995, the American Pain Society issued a consensus statement regarding the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. They recommended that medical professionals track pain intensity on a patient’s chart, and update the value regularly. Pain above a chosen threshold (which could be determined locally) should trigger action.

Later, the American Pain Society would be excoriated for pushing drugs, and using this statement as part of their agenda. The critics were…not completely overreacting. It’s hard to read the paper without concluding that health care workers are expected to hurl OxyContin at patients like a teppanyaki chef flinging shrimp at diners.

Indeed, any other sort of pain management strategy is treated as an afterthought. The authors write, “[T]his guideline focuses on the assessment of pain and its treatment with analgesic drugs, which we consider to be the two most important components of the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, non-pharmacological measures can also contribute to effective therapy.”

Their proposed patient questionnaire included items like, “If you still have pain, would you like a stronger dose of pain medication?” Patients who answered “No” were asked to explain themselves.

Perhaps the authors were thinking of that old business adage, “What gets measured gets managed.” They pointed out that busy doctors and nurses often failed to accurately assess a patient’s pain. If they didn’t ask about pain specifically, they were prone to underestimate its severity.

In 1996, James Campbell, MD, included the phrase “pain as the 5th vital sign” in his presidential address to the American Pain Society, and it became the title of an American Pain Society campaign.

Dr. Campbell said, “Vital Signs are taken seriously. If pain were assessed with the same zeal as other vital signs are, it would have a much better chance of being treated properly. We need to train doctors and nurses to treat pain as a vital sign. Quality care means that pain is measured and treated.”

“Pain: the 5th Vital Sign” was taken up by the Department of Veteran Affairs for their own pain management campaign in 2000.

This strategy specifically called for using a 0–10 numeric pain rating scale. Patients were supposed to be regularly assessed, and have their pain levels recorded in their medical record.

Pain Scales Become the Standard

In 2001, The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now simply known as The Joint Commission) got on board, and introduced a new set of pain management standards. The Joint Commission is a major accrediting body for U.S. medical facilities, so their standards came with the specter of punishment for non-compliance.

However, shortly after The Joint Commission released their guidelines, reports began to trickle in regarding overuse of opioids. Of particular concern were reports of patients who died of respiratory depression caused by pain medications after surgery.

The commission quickly walked back its wording, or at least tiptoed back quietly. From 2001 to 2002, the phrase, ““Pain is considered a ‘fifth’ vital sign in the hospital’s care of patients” was demoted, and replaced with, ““Pain used to be considered the fifth vital sign.” Two years later, the reference to vital signs vanished entirely.

By 2009, when opioid use was deemed sufficiently problematic to be called a crisis, The Joint Commission removed the requirement for mandatory pain assessments (except in behavioral health care situations).

Current versions of The Joint Commission’s Pain Assessments and Management Standards include information on non-pharmacological pain management, and the responsible use of opioids.

In a JAMA editorial, Dr. David Baker, the Executive Vice President of The Joint Commission’s Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, pointed to the hard place across from the rock of opioid overuse. “[I]t is necessary to carefully acknowledge concerns that patients with chronic, painful conditions may be undertreated and stigmatized if they need adjunctive opioid therapy.”

Early Controversy

Camp prescribe more faced opposition from the start. In 2002, the Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy ran a commentary titled, “Pain Scales Don’t Weigh Every Risk” coauthored by the President and Vice President of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

The paper acknowledged that patients were often undertreated for pain, but it also pointed out that, “Adverse drug events due to opioids have increased with the recent adoption of pain management standards by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.” In the staid world of academic communication, them’s fighting words.

The authors also noted that patients were being overly sedated, or not closely monitored. Medical professionals failed to factor in other health conditions, such as sleep apnea, that put a patient at greater risk.

The authors also observed that some patients were more sensitive to pain than others. Or at least, some patients overreported the severity of their pain, while others underreported it. If doctors and nurses took each rating at face value, it could lead to overtreating some patients (and exposing them to unnecessary risks), and undertreating others.

Truth and Consequences

Were the thought leaders inside the American Pain Society, Department of Veterans Affairs, The Joint Commission, and other pro-medication groups to blame for the rise in opioid use, or were they simply swept up in the tide?

It’s impossible to say with any certainty, but one fact was clear: The number of opioid prescriptions rose significantly through the late 90s and early 00s.

The arrival of OxyContin in 1996 did nothing to dissuade doctors from reaching for their prescription pads. The drug’s manufacturer, Purdue Pharma, claimed that OxyContin’s slow-release formula discouraged abuse. The FDA approved the use of these claims, and Purdue’s sales reps assured doctors that the risks of addiction were miniscule.

The sales reps also pushed into new markets, and convinced primary care doctors (and other non-pain specialists) that OxyContin was perfectly safe, and appropriate for treating a broad range of chronic pain conditions.

But this party, fueled by pills and money, couldn’t last forever. Rising rates of addiction and overdose deaths, and the increasing abuse of non-prescription opioids showed that these pills had society-wide side effects.

None of the major groups that advocated opioid use would escape unscathed, although the level of damage they suffered varied significantly.

The American Pain Society, which coined the phrase “pain as the 5th vital sign,” filed for chapter 7 bankruptcy and dissolved in 2019. Their press release explained that, “Over the past year, APS has been named a defendant in numerous spurious lawsuits related to opioids prescribing and abuse.”

Then-President William Maixner, DDS, PhD, went on to say that it was, “[P]ointless to continue operations just to defend against superfluous lawsuits. Our resources are being diverted to paying staff to comply with subpoenas and other requests for information and for payment of legal fees instead of funding research grants, sponsoring pain education programs, and public policy advocacy.”

Facing its own mountain of litigation, Purdue Pharma filed for the less-final Chapter 11 bankruptcy last year. On October 21st, 2020, the company pled guilty to three felonies, and agreed to pay $8.3 billion in fines. Plenty of other lawsuits are still outstanding, and Purdue’s saga is still playing out.

Current Practice

Not surprisingly, the U.S.’s perceived overreliance on opioids has prompted much soul searching in medical and government circles. New practice guidelines stress multimodal methods of pain assessment and treatment, and put flowcharts around opioid prescribing.

Have doctors moved away from pick-a-number pain scales in this new, enlightened world? Are they finally ushering in nuanced diagnostic tools that acknowledge the complex nature of pain?

Hahaha! Don’t be silly. Basically, it’s business as usual, but with a new rush to embrace non-opioid options. Approved alternative treatments include music therapy, tai chi, mindfulness, and prayer. I fully expect to find, “Have Mommy kiss the boo-boo and make it go away,” in the next editions.

Pain assessments are in a weird place. They’ve become embedded in common practice, but the ideology that led to their use is in question. There seems to be little agreement (or even much discussion) about new methods or objectives.

The Pain Management Best Practices report released by the Department of Health and Human Services, mention the need for better pain assessment practices, but shies away from specifics. Meanwhile, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement’s Pain: Assessment, Non-Opioid Treatment Approaches and Opioid Management Care for Adults report makes a passing reference to pain scales, but stress the need for a comprehensive assessment and “Shared decision making.”

Much more space is devoted to performing risk assessments before prescribing opioids, and considering psychosocial factors. The impact of these guidelines remains to be seen, but the focus on psychological and social factors gives me pause.

Most doctors who are overseeing pain management are not trained psychologists or sociologists. How exactly are they supposed to do these evaluations? However well-intentioned these guidelines are, they provide an excuse to say, “You sound anxious. Why don’t you try meditation, instead of medication?”

I’m not sure if I’m comforted or frustrated, knowing that my pain rating doesn’t matter. Even if it did, the best result would be more pain meds, which I could ask for, even without a pain rating. But at least I can stop worrying that I’ve failed some secret test. Maybe next time I’ll ask, “Why are you asking my about my pain?” to see if they get the right answer.

Photo courtesy of Lord Belbury via Wikimedia Commons.

References

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). (2019). Pain: Assessment, Non-Opioid Treatment Approaches and Opioid Management Care for Adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Retrieved from https://www.icsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Pain-Interactive-7th-V2-Ed-8.17.pdf

- Brian F. Mandell, M. P. (2016, June 1). The fifth vital sign: A complex story of politics and patient care. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 83(6), 400-401. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83b.06016

- David W. Baker, M. M. (2017, March 21). History of The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Lessons for Today’s Prescription Opioid Epidemic. JAMA, 317(11), 1117-1118. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0935

- David W. Baker, M. M. (2017). The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Origins and Evolution. The Joint Commission, Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, Oakbrook Terrace, IL. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/pain-management/pain_std_history_web_version_05122017pdf.pdf?db=web&hash=E7D12A5C3BE9DF031F3D8FE0D8509580

- Department of Health & Human Services. (2019). Pain Management Best Practices: inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

- Geriatrics and Extended Care Strategic Healthcare Group. (2000). Pain as the 5Th Vital Sign Toolkit. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf

- Hoffman, J., & Benner, K. (2020, October 21). Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Criminal Charges for Opioid Sales. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/21/health/purdue-opioids-criminal-charges.html?searchResultPosition=3

- Hoffman, J., & Williams Walsh, M. (2019, September 15). Purdue Pharma, Maker of OxyContin, Files for Bankruptcy. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/health/purdue-pharma-bankruptcy-opioids-settlement.html?searchResultPosition=9

- Marks, R. M., & Sachar, E. J. (1973, February 1). Undertreatment of Medical Inpatients with Narcotic Analgesics. Annals of Internal Medicine, 78(2), 173-181. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-78-2-173

- Max, M. B. (1990, December 1). Improving Outcomes of Analgesic Treatment: Is Education Enough? Annals of Internal Medicine, 113(11), 886-889. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-885

- Max, M. B., Donovan, M., Miaskowski, C. A., Ward, S. E., Gordon, D., Bookbinder, M., . . . Edwards, T. (1995, December 20). Quality Improvement Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. JAMA, 274(23), 1874-1880. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03530230060032

- MD, A. V. (2009). The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 221-227. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714

- N. Levy, J. S. (2018, January 19). “Pain as the fifth vital sign” and dependence on the “numerical pain scale” is being abandoned in the US: Why? British Journal of Anaesthesia, 120(3), 435-438. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.098

- Wigal, D. (2014). Opium. New York: Parkstone International.

One thought on “Why Do I Have to Rate My Pain on a Scale of 0–10?”