As I was investigating reherniation rates and the effectiveness of microdiscectomies, I came across a paper that sought to answer a question I hadn’t thought to ask – does the type of disc herniation matter?

A 2003 study from Stanford University followed up with 180 sciatica patients who underwent a microdiscectomy. The participants were limited to those with an MRI-confirmed disc herniation who had never had spine surgery before.

Four Categories of Disc Herniations

While operating, the surgeon grouped the types of herniations into four categories, depending on the damage to the annulus.

- Fragment-Fissure: This was the most common type of defect, found in 49% of patients. The annulus had a small, slit-like hole from which some nucleus material oozed out. The surgeon removed nucleus fragments through this hole.

- Fragment-Defect: This was the third-most-common type of defect, found in 18% of patients. The annulus had a wide (>6 mm) hole from which some nucleus material oozed out. The surgeon removed the nucleus fragments through this hole.

- Fragment-Contained: This was the second-most-common type of defect, found in 23% of patients. The annulus was undamaged, but nucleus fragments were contained within. A surgeon cut through the annulus to remove the fragments.

- No Fragment-Contained: This was the least common type of defect, found in only 9% of patients. The annulus was undamaged, and there was no detached fragment of nucleus material. A surgeon removed parts of the bulging disc, a procedure which left large holes in the annulus.

Two years after the surgeries, researchers followed up with the patients, and gave them questionnaires meant to assess their disability levels, pain levels, satisfaction, and medication usage.

How Did the Four Groups Fare?

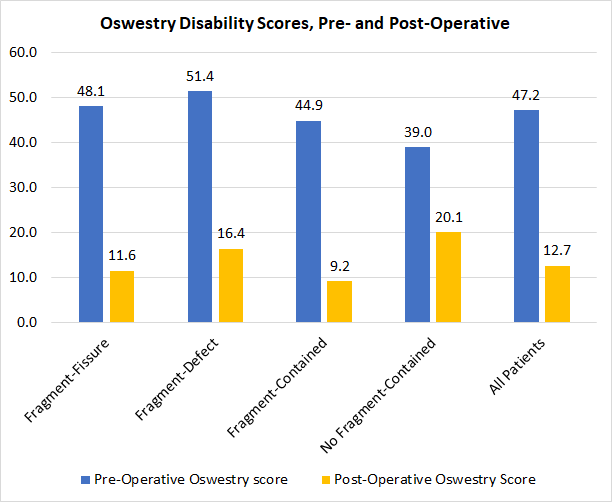

The encouraging news is that all four groups of patients reported significantly lower levels of disability after the surgery, compared to before.

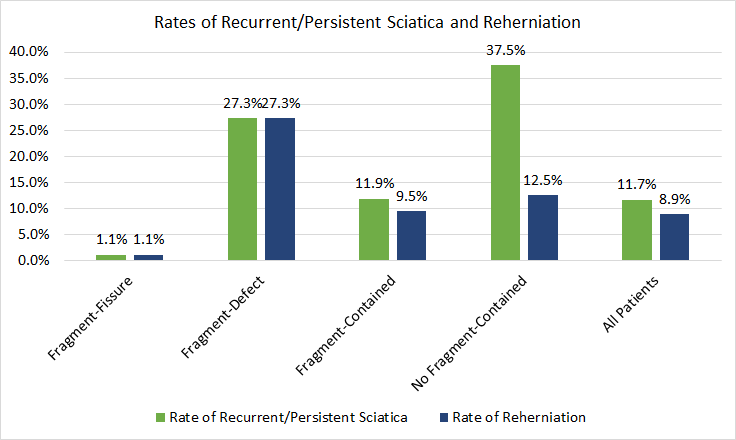

However, there were also large differences among the groups. The patients classified as fragment-fissure had the best outcomes. Their rates of persistent sciatica and documented reherniation were both 1.1%.

Patients in the fragment-contained group had results that were good, but not quite as stellar as the fragment-fissure group. Their rate of persistent sciatica was 11.9%, and their rate of documented reherniation was 9.5%.

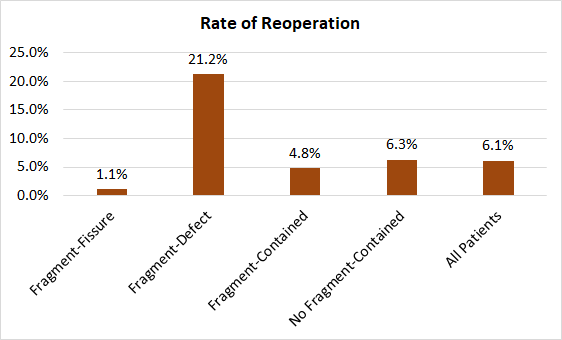

Those in the fragment-defect group seemed uniquely predisposed to re-injury. Their rate of persistent sciatica and documented reherniation were both 27.3%. They also had the highest rates of reoperation, at 21.2%.

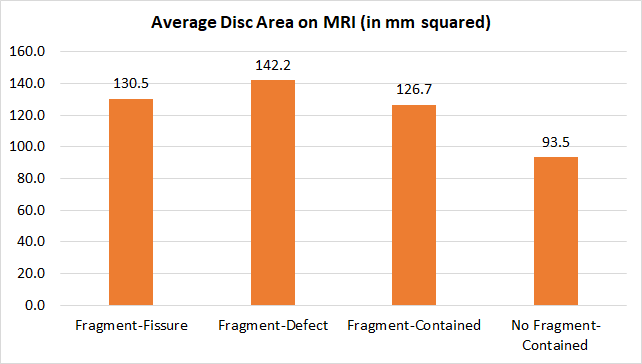

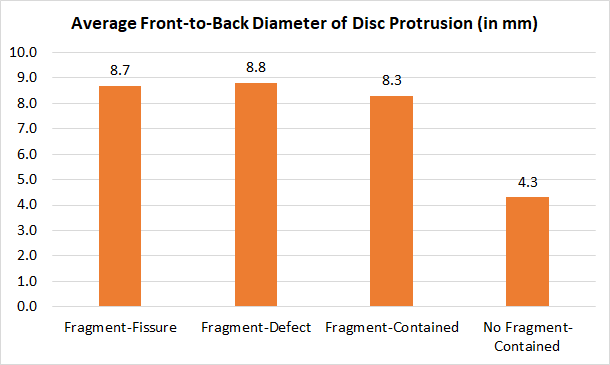

The most confusing results came from the no fragment-contained group. For starters, their discs were smaller than anyone else’s. Their disc diameter and disc area were significantly smaller than those of the other groups. It isn’t clear what, if any, effect these differences had on their pain, or on their response to surgery.

Their rate of persistent sciatica was 37.5%, though their reherniation rate was only 12.5%. In the other groups, rates of reherniation and persistent sciatica tracked closely.

Of the six patients in that group who reherniated, only two showed distinct, new-fragment herniations at the same level. The other four showed broad-based disc bulges. In contrast, all the patients in the fragment-defect group who reherniated showed new fragments at the same level.

This data, combined with the no fragment-contained group’s worse disability and pain scores, indicates that these patients got the least benefit from surgery.

Study Shortcomings

Although these results are intriguing, the study did have some significant shortcomings, including:

Defects Based on Operative Findings. For patients, the most vexing problem is that it’s difficult to make practical use of this information. The type of defect was determined “on the basis of operative findings,” meaning the surgeon had to cut the patients open before classifying their disc defects.

As a patient, I’d like to know which group I fall into before I agree to surgery.

No Control Group. One noticeable feature of this study was the lack of a control group. That means that it’s impossible to say whether the patients who had a microdiscectomy fared better than patients who opted not to undergo surgery.

Limited Follow-Up MRIs. Another annoying study design issue was that during the follow-up period, only patients who reported recurrent sciatica had a second MRI. It’s impossible to know how many, if any, of the patients had asymptomatic reherniations.

Lack of Detail. In places, the paper was frustratingly vague. There were no images of the various types of defects, and the descriptions given were hardly exhaustive.

The surgical details were also sparse. The procedures performed on the no fragment-contained group weren’t self-explanatory, and I would have appreciated specifics.

Some patients underwent a laminotomy or facetectomy so that the surgeon could better access their disc, but there was no data to say which patient got what.

Unclear Timeline. The follow-up timeline was also murky. The authors reported that they followed up with patients at a minimum of two years, though the median was six years. It was not clear whether all patients were followed for a certain length of time, or whether each was interviewed at a single point in time.

There’s no telling when reherniations occurred, and there is no distinction made between recurrent and persistent sciatica. This means it’s impossible to say how many patients continued to have sciatica, and how many showed temporary improvement before their symptoms returned.

Takeaways

This study suggests that the type of disc herniation might predict how patients fare after a microdiscectomy. Those with a tiny, slit-like hole in the annulus and extruded disc material are most likely to do well. These patients had the lowest rates of reherniation and persistent sciatica.

Patients with large annular defects are significantly more prone to reherniation and recurrent sciatica, and had the highest rates of reoperation.

Patients in the no fragment-contained group benefitted the least from a microdiscectomy. Their post-operative ratings of pain, disability, and satisfaction were the worst of any of the groups. When they reported persistent pain, MRIs were less likely to detect any problems that could be corrected with surgery.

Although these findings are interesting, patients may have a hard time applying the lessons to their own decision-making. Since the type of herniation was classified during surgery, patients were not aware of their herniation type before they went under anesthesia.

One thought on “For Microdiscectomy Success, Does the Type of Herniation Matter?”