Every so often, I’ll read a book that takes my snippets of observation and places them in the context of a larger conceptual framework. The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care –and How to Fix It was absolutely one of those books. If you’re an American who wants to know what the heck is wrong with our health care system, then this book is for you.

While the style is refreshingly straightforward, the book itself is not an easy read. I got queasy at times. It was hard to stomach the tales of patients driven to bankruptcy by inflated medical bills, or hospitals that routinely sued low-income patients. But while the author didn’t shy away from tales of devastation, he also highlighted people and companies that are trying to bring sanity to a crazy system.

Some sections, such as the critique of workplace wellness plans, felt obvious and underdeveloped. But on the whole, this is the most insightful, enlightening, and engaging book I’ve read about American health care.

A View from the Inside

Makary, a surgeon and researcher from Johns Hopkins Hospital, is very much a medical insider. But rather than playing defense with lines like, “hospitals need to cover uninsured patient care – that’s why we charge so much,” or, “overtreatment is a defense against malpractice,” he offers a thoughtful critique of the system, from within the system.

For example, pancreatic surgery (his specialty) has a high rate of complications, regardless of how competent the surgeon is. Pancreatic surgeons are going to have higher readmission rates than, say, ENT specialists. Besides, surgeons who really want to lower their complication rates can perform unnecessary procedures on healthy people. For these reasons, measuring surgeons by their complication or readmission rates can be deceiving.

Instead of using these well-intended but misleading metrics, Makary believes in finding specialty-specific measures, and letting doctors know how they rate compared to their peers. Many doctors are naturally competitive, and this approach harnesses their desire to one-up each other.

Makary doesn’t just offer armchair advice. His Improving Wisely campaign takes exactly this approach. For example, he worked with a professional association of skin cancer surgeons to collect data on how many slices of tissue doctors took to excise a cancerous growth. Most surgeons averaged one to two, but some outliers averaged over four. Since they bill by the slice (or “stage”), the outliers were probably overtreating and overcharging.

A year after the skin surgeons got their results, 83% of the notified outliers had lowered their average. The results were even more striking considering that no one was punished, or even officially chastised.

Makary’s attitudes are contagious, because he offers them so earnestly. When he describes new 4K monitors that display videos of microscopic structures during surgery in exacting detail, I could practically see him salivating. When he went on to describe how hospital purchasing committees might consider the old screens, “clinically acceptable,” and decline to purchase the new screens (without consulting the surgeons), the pain and frustration were real.

But although Makary has the heart of a surgeon, he shows unusual empathy towards the CEOs, insurance brokers, patients, and others who are enmeshed in the system. He’s not afraid to sling mud, but first he takes careful aim.

.Actually, I made that up. But it certainly wouldn’t be the worst decision Brooks Brothers has ever made.

What’s This Going to Cost?

About six years ago, after I finally got a publishing job with health insurance, I went to a hospital to have some gynecological tests done. I had only the faintest idea of what my health care plan covered, so before I agreed to any tests, I asked what they cost.

“The cost?” the nurse asked, puzzled. She scrunched up her face, thinking. “I really don’t know.”

“Who does know?” I asked.

“Let me see what I can find,” she said, and left.

After a few minutes, I was brought over to the billing department, where I was passed from desk to desk, and finally made to wait while someone consulted the Oracle of Delphi, or did whatever it is they do. I was eventually handed a list with some highlighted lines.

Once I realized I had enough money in savings to cover the bill if need be, I agreed to have the tests done. But I was weirded out anyway. The medical staff clearly had no idea what things cost. Even in the billing department, most of the employees seemed confused by the question, and finding the price seemed to require as much research as a master’s thesis.

I remember wondering how on earth this hospital functioned when not even the billing staff knew what they were charging.

This, as it turns out, is typical. Makary points to one study in which researchers called 101 hospitals in the U.S. and asked what a specific type of heart bypass surgery would cost. Only 53 hospitals could even find a quote. And the costs they cited ranged from $44,000 to $448,000. Worse, the hospitals who charged ten times as much as their competitors didn’t necessarily have better outcomes – the data showed no correlation between price and quality.

I’m no economist, but even I know that in fair market, prices for similar products should converge. So what’s up with this bizarrely wide spread?

Makary compares the U.S. healthcare market to the Khan el-Khalili bazaar in Cairo. None of the items for sale in that sprawling, open-air market have price tags. Instead, vendors and customers haggle until they reach an agreement. As Makary writes:

The Arabic merchants are so good they have a global reputation for their sales tactics. They track your eyes to see what you look at twice and what makes you smile. If you ask the price of an alabaster replica of one of the famed Egyptian pyramids, they tell you it’s $100. It may be worth $1. Some tourists fall into the trap and fork over the full price. Others nervously ask for a small discount and then pat themselves on the back for paying $90. The real wheeler-dealer shoppers counteroffer even lower and negotiate the price down to $50. They walk away bragging about their great deal. But it’s the merchant who invariably wins. That’s the markup and discount game.

Except, in the health care system, the customer is less likely to be a person and more likely to be an insurance company. Each year, insurance companies demand steeper and steeper discounts from health care providers. The hospitals are happy to agree – they mark up their prices, and voila! Both sides walk away feeling like they’ve won.

But No One Really Pays Those Prices, Right?

It’s a common refrain among doctors, administrators, and even patients: No one actually pays the full sticker price. It’s just there for show.

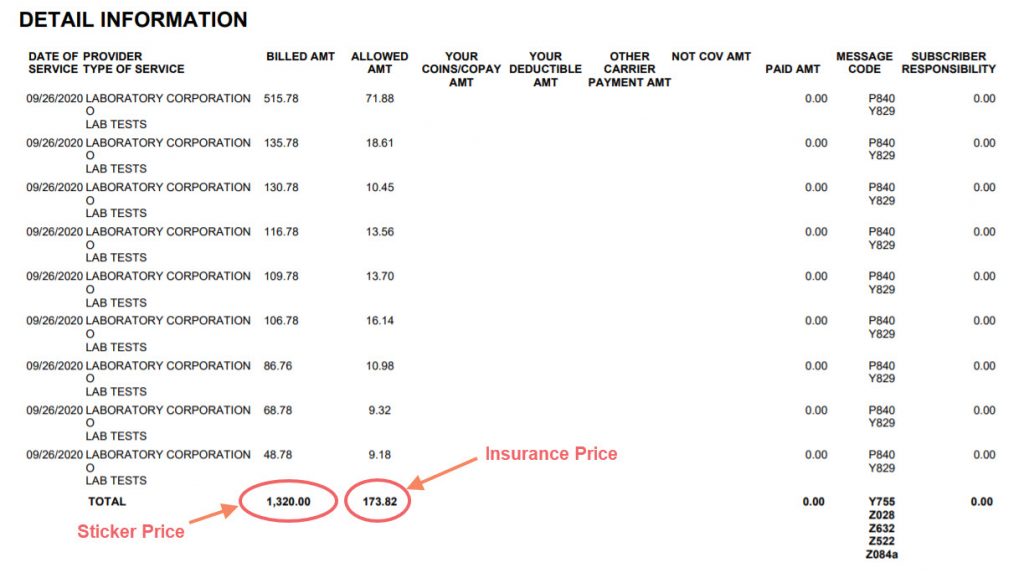

To judge from my own medical bills, insurance companies only pay a fraction of the procedure’s theoretical costs. This financial chicanery is unsettling, but I put it in the category of Problems That I Can Ignore for Now. (Other problems in this category include the honey bee die-off, and where I’m supposed to bring dead batteries.)

But Makary found countless examples of people who were expected to pay full price, including a friend of his who was charged $10,000 when the hospital removed a skin tag from her finger. When Makary intervened on her behalf, he ran up against the bulwarks of medical bureaucracy. He and his friend both had to fax in their patient privacy authorization forms, after which Makary had to mail in a request for an itemized bill, and a paper check for $25.

After months of delay, Makary was finally allowed to speak to a billing representative. He requested that the hospital reduce the bill to the Medicare-allowable amount of $750. The representative’s response was, “The law allows us to charge whatever we want. If we want to charge a million dollars, she has to pay it.”

In the end, Makary’s friend paid the full price (one-sixth of her household’s annual income), to avoid further damaging her credit.

The bizarre twists of medical pricing were illuminated in Makary’s story about an Amish community in Indiana. The Amish are uninsured, but when one community member needs medical care, the entire community will pool funds to pay the bills.

The leader of the community contacted one of Makary’s colleagues (who also studies hospital markups), and asked for help dealing with an astronomical bill. A child in the community had suffered significant complications at birth, and the child’s father received a bill for $1 million. Had the man been insured, the bill would have been closer to $300,000. Which certainly ain’t cheap, but which is less than a third of what the man was asked to pay.

Ironically, the Amish helped build the hospital that was price gouging them.

Makary’s colleague knew the leader of the hospital, and after talking the case over, the bill was reduced to less than $200,000. So all’s well that ends well. But the hospital’s decision to lower the bill seems less than magnanimous when you consider how inflated it was in the first place.

That message isn’t lost on the Amish. During a visit to a Pennsylvania Amish community, Makary leans that some Amtrak trains are half full of Amish taking the six-day trip to Mexico for medical care.

Makary gives numerous examples of medical billing gone awry, many of which were enough to make my head spin. For example, a French tourist had a minor heart attack while traveling in the U.S. After he was stabilized with medication, the U.S. hospital suggested he undergo a $150,000 heart bypass surgery.

The tourist then called a heart surgeon in his native France, who assured him he could have the same operation there for the equivalent of $15,000. The man decided to postpone surgery until he was back in his home country. When he informed the hospital staff of his decision, they spontaneously dropped the price to $25,000.

Makary himself sums up the problem:

The game is absurd. Think of the problem of being out-of-network. The recommended solution is to join the network. The game proposes a solution that exists only because it created the problem in the first place. The network is both the firefighter and the blaze. It’s the savior and bogeyman, the police officer and perpetrator. We have come to accept this as standard operating procedure in the business of medicine. But somebody needs to ask: Did anyone ever intend things to get this bad? While networks served a purpose, they are now the very reason we have surprise bills and lives ruined by financial toxicity.

Surprise! It’s a Bill!

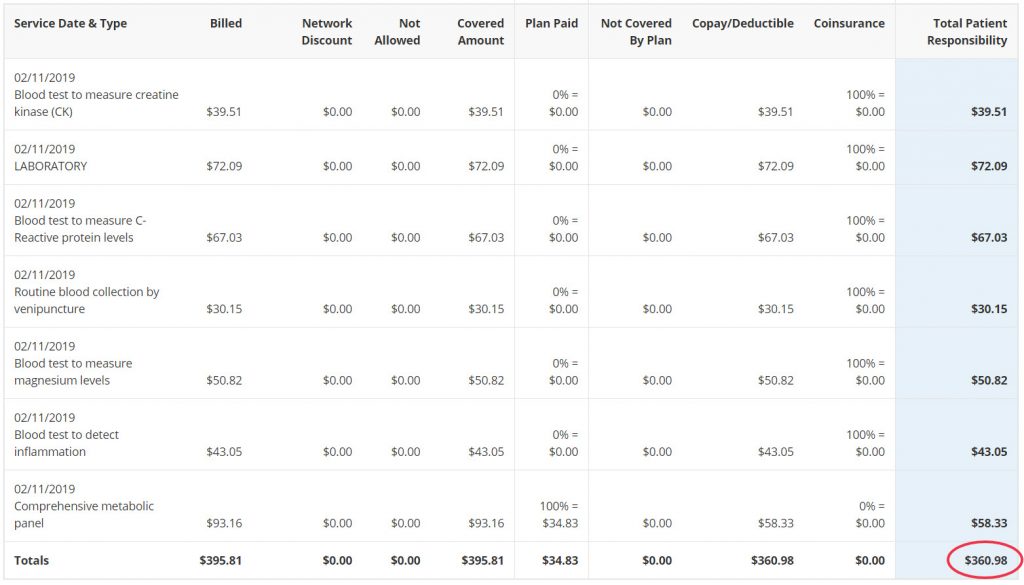

Before I visited the Mayo Clinic in February of 2019, I called my insurance company to make sure the hospital was in-network. No problem, they told me. Everything will be fully covered.

When I arrived, I checked with the Mayo Clinic staff, and they too confirmed that my insurance should cover any charges.

I was surprised, then, when a few months later I got a bill in the mail for $360.98. Apparently, some of the prescribed blood tests hadn’t been covered by my insurance, and I was on the hook. I was confused, since my blood had been drawn in the Mayo Clinic, by Mayo Clinic staff, and as far as I knew, no other company had been engaged for lab work.

Fortunately, I had enough in savings to cover the bill, so it was only an annoyance. Makary showed me that I wasn’t alone. In fact, I’m luckier than most Americans. He writes:

Surprise bills are common. In 2015, the Consumer Reports National Research Center estimated that 30% of Americans received a surprise medical bill. But just three years later, another study found it was about double that figure. The University of Chicago reported that 57% of Americans received a surprise bill in the previous year. Another study of New Mexico residents found that more than half of people who had gone to the emergency room got a surprise bill.

Perhaps the most egregious surprise bills come courtesy of private air ambulance services. It seems that even helicopters can’t rise as fast as their prices.

One patient in rural Montana went to his local hospital with stomach cramps. The doctors there insisted that he fly into a big city hospital for intensive treatment.

The big city hospital was short on beds, so they left the man on a stretcher in the hallway. The doctors ran a battery of tests on him, concluded he was fine, and pestered him to go home so they could free up space.

A few months later, the man got a bill for nearly $400,000. The helicopter ride alone cost $60,000. And, unbeknownst to the patient, the big city hospital was out-of-network.

In a separate case, a man in Texas suffered a rattlesnake bite, and took a helicopter to a hospital in Abilene. The bill he got showed an obligation of $43,514. The man commented that receiving the bill, “[W]as actually more traumatic than when I realized I was bitten by a rattlesnake.”

As unbelievable as these prices are, they’re even more shocking when you realize that 80% of air ambulance transfers are for non-emergencies. Many transfers of stabilized patients could be handled using a ground ambulance for a fraction of the price.

What Else Could Go Wrong?

Makary covers an admirable amount of territory in this slim, 267-page book. In addition to the topics covered above, he explains:

- Why South Korea’s improved thyroid cancer screening rate (and subsequent interventions) didn’t save lives.

- Why you should be skeptical of vascular surgeons who offer free screenings at health fairs.

- How group purchasing organizations’ decisions lead to shortages of standard medical supplies like saline bags, epinephrine, and heparin.

- How to find out what hospitals are paid to perform standard procedures.

- Why your pharmacy benefits manager really wants you to sign up for mail-order prescriptions.

- Why many U.S. doctors overprescribe opioids.

I plan to re-read once my initial disorientation has worn off. In particular, I’ll have to return to the chapter on Carlsbad Medical Center, which stuffs the civil court docket with lawsuits against patients. The sort of predation practiced by Carlsbad Medical Center would make a mob boss sick.

While many of the problems in our health care system can’t be directly solved by patients, this book at least gave me a framework for understanding some of the largest problems, and offered promising alternatives.

If nothing else, I can now confidently say, “No thank you. I don’t need a balloon in my leg.”

One thought on “Book Review: The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care – and How to Fix It by Marty Makary, MD”