Ten years ago, Claire M. had the contours of her life plotted out. She worked part-time doing customer service and other odd jobs for her husband’s employer, but the better part of her energy was spent taking care of her family.

Her oldest son, born in 2002, had a rare genetic anomaly. A section of his DNA had been duplicated, which caused autism-like behaviors, a deformity in one foot, and an inability to sweat.

Claire’s younger son wasn’t classified as special needs, but like all children, the six-year-old boy needed attention and love.

Claire hadn’t expected to become a full-time caregiver, but she hadn’t expected to have a special-needs child, either. Sorting out his medical appointments and fighting with the insurance company took time, and someone had to do it. She became known among her friends as the person who could always find accurate medical information.

Claire had a master’s degree in English literature, and thought she would some day write a book about her son’s struggles. She didn’t expect that soon, her own medical needs would become the central drama of her family.

Whispers of Trouble

In the summer of 2013, Claire noticed a strange pressure in her left ear. Sometimes it felt like a trickle of water was carving a path from her ear down to her throat. She started getting dizzy, and her balance was off. She figured she had an ear infection, or maybe a problem with her sinuses.

But whatever it was, she could deal with it later. That fall, her husband got an amazing job offer from an electrical device manufacturing company. They offered him work as a product manager, and threw in a generous relocation package.

That last provision was important. Claire’s family lived in Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains. The job was in New Orleans. They had thirty days to get their house on the market, and find temporary lodgings in Louisiana before her husband had to report to work.

Claire didn’t have time to worry about a minor ear problem. Instead, she started calling moving companies, and packing boxes full of their things. She was excited to trade their isolated existence in the hills for a suburban neighborhood and warm winters. But she was also stressed about the sheer amount of work it would take to finish everything in time.

She figured that was why she started to freak out about the smallest things.

Once, while her husband was away on business, she woke up in the middle of the night and couldn’t feel her right leg at all. She was seized by panic, and wasn’t comforted when Google told her she might have one of many gruesome neurological conditions.

And then, there was the autumn day when she was walking through her own backyard, and became terrified of stepping on the acorns that littered the ground.

She’d grown up in the Northeast, and lived there most of her life. She knew about oak trees and acorns, and they were silly things to be afraid of. Why was an acorn-covered yard now making her heart race? Why couldn’t she put aside the certainty that she’d trip and fall?

It got worse. Before the move, Claire went to the mall to pick up a pair of eyeglasses. It was a weekday, and the mall wasn’t terribly crowded, but the bright lights, piped-in pop music, and tangled knots of shoppers overwhelmed Claire’s senses.

She was petrified. Physically, she couldn’t move. She ordered her feet to take a step, but they were locked in place, and wouldn’t budge. She was terrified, too, both by the unexpected harshness of the environment and her body’s reaction to it.

If she was going to have a breakdown, why did it have to be in public? Claire prayed that no one would notice. She didn’t want people swarming over her and making a fuss. She just wanted to get out of the mall, and pick up her boys from school as planned.

She held on to the wall as casually as she could, until her muscles loosened enough to allow her take a few awkward, mincing steps. All Claire could think about was making it out of the mall, and into her car. Once she got there, she would be okay. She didn’t know how she knew that, but the thought sprang into her head with the full force of conviction.

She navigated her way out of the mall slowly, and kept close to the wall in case she needed support. It took an eternity, but she finally picked her way across the floor of the department store, and over the parking lot, and made it into the safe enclosure of her car. She took a few minutes to relax and breathe, and then drove to school to pick up her kids.

She didn’t tell them what had happed that day. She didn’t tell anyone. For now, she thought, they should all focus on the move. Anyway, the episode was probably due to stress. Claire soothed herself by saying she just needed to get to Louisiana, and then everything would be alright.

She wouldn’t be so lucky. Claire didn’t mean to carry her symptoms across state lines, but she couldn’t leave them behind, either.

New Setting, Same Symptoms

Her ear problems never really went away. Once Claire had the time and insurance, she visited an ear, nose, and throat doctor, who failed to find anything obviously wrong. He thought she might be suffering a cranial leak, which would explain the strange sensations, and possibly her disorientation.

He injected dye into her spine, placed her on an inversion table, and subjected her to a CT scan. When that failed to reveal anything out of the ordinary, he was stumped, and referred her to a neurologist.

Claire also visited a back doctor, who she thought might be able to explain her strange movement glitches and occasional paralysis. The back doctor ordered x-rays and MRIs, and sent Claire to physical therapy, but this also proved to be wasted effort.

In January of 2014, Claire went outside to mow the lawn, and found she couldn’t do much of anything. Her brain sent messages to her muscles telling them to move, but the instructions were ignored. She was rendered as immobile as a statue.

When her legs finally unfroze, Claire went back into the house, and started sobbing. She begged her husband not to go on the work trip he had scheduled the next day. She didn’t care that she was in a nice, suburban neighborhood, and help was only a cry away. She didn’t care that her two sons would still be home. Her husband would leave, and she would lose the ability to walk. The connection was clear in Claire’s mind.

That summer, Claire and her family travelled to North Carolina to visit her in-laws. Her husband’s parents were celebrating their 50th anniversary, and the whole extended family was invited to the party.

It was supposed to be fun, and Claire tried to pretend that it was. But the trip was a series of strange and inexplicable torments. The airport was bad enough, with its crowds, constant announcements, fast food smells, and rows of newsstands. Claire’s husband insisted on giving her his noise-cancelling headphones, but the electronic gadget couldn’t mute the sights, or smells, or vibrations.

The hotel should have been better. It was a tranquil and stately retreat, nestled among copses of hardwoods and conifers. It catered to wedding parties, golfers, and corporate retreats. But Claire arrived flustered and disoriented, and the hotel proved to be a perilous landscape to navigate.

Maybe it was her ear problem, but the elevator threw her off-balance. Whenever it spat her out onto a new floor, Claire stumbled like a sailor getting reacquainted with land.

The bold, geometric patterns in the carpet also messed with her head. They seemed to warp her perception of space. She couldn’t navigate her way across the floor, and she was terrified she’d lose control and fall. “I was trying to walk without looking like I’d already had three martinis at the bar,” Claire recalled. She questioned her choice to wear high-heeled shoes.

But it wasn’t just the sensory distortions. An aura of doom hung over the party, and she couldn’t wish it away. Claire was filled with heart-pounding anxiety, worse than anything she had felt before. Her best days were behind her. She didn’t know how she knew, but she did, and she was overcome by nostalgia.

It was like being in the third act of a Shakespearean tragedy. People swirled around Claire in currents of joy, and love, and festivity. The atmosphere was saturated with life. Fifty years of marriage! One big, happy family!

But this was the apex. Moments like this would never come again. A curse was about to fall, and the play’s denouement would chronicle their inevitable decline and demise.

Claire alternated between playing the carefree guest – “You have to come down and see us sometime! We’re looking forward to Mardi Gras!” – and sobbing in the bathroom.

When she got home, Claire spent the rest of 2014 and the beginning of 2015 visiting doctors, but none of them could explain what was wrong. Some assumed that anxiety itself was the problem. When she told them about her irrational fears and random moments of panic, they chalked it up to an anxiety disorder, or early menopause.

But that didn’t explain her unresponsive muscles. Her rheumatologist considered ankylosing spondylitis, which might explain her stiffness, but her vertebrae weren’t fused, and she lacked the telltale inflammation markers.

She tried visiting a chiropractor, but he dismissed her without treatment. Her trunk was too stiff, and he couldn’t adjust her spine. That was just as well. The carpet in his office was nearly as disorienting as the one in the hotel, and it threw her off balance.

The anxiety was indeed baffling. She knew about depression. She had fallen into that pit as a teenager, and waded down again after her children were born. But anxiety? That was new. She lived in fear of something she couldn’t name.

One in a Million

In July of 2015, Claire reconvened with her rheumatologist, who barely looked old enough to be a practicing doctor. He reviewed her negative test results, and offered a new interpretation of her symptoms.

“I think you have something called stiff man syndrome,” he said. “We learned about it in med school. It’s extremely rare, but your symptoms fit.” He recommended she see a movement neurologist, and get an EMG.

In the parking lot, Claire sat and Googled the condition on her phone. The tidbits she caught were not encouraging.

- Stiff person syndrome is a rare autoimmune movement disorder that affects the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord).

- The main symptoms of Stiff Person Syndrome are muscle stiffening in the torso and limbs, along with episodes of violent muscle spasms. These can be triggered by environmental stimuli (like loud noises) or emotional stress.

- Most individuals with Stiff-Person syndrome have frequent falls and because they lack the normal defensive reflexes; injuries can be severe.

- SPS occurs in about one in a million people and is most commonly found in middle-aged people.

- It is unclear whether the disease process underlying SPS is directly responsible for anxiety disorders or whether anxiety disorders develop as a reaction to disability associated with SPS.

Claire started to cry. One in a million? She thought. I’m not that special!

The movement neurologist didn’t think Claire was that special either, and rejected the stiff person syndrome diagnosis. She suspected Claire had a more common condition, like Parkinson’s or Lou Gehrig’s disease. She ordered another series of tests, which revealed nothing.

Much as Claire disliked the stiff person syndrome diagnosis, at least it was something. Now, Claire felt like she was once again a medical mystery.

The summer of 2015 was tough. The muscles in Claire’s back and legs stiffened so much that she couldn’t coax enough bend out of her joints.

When school resumed in the fall, Claire went to a PTA meeting. She had started volunteering with PTA almost as soon as her new home was set up, and quickly made friends with the other parents. Some of them proved to be more observant than she would have liked.

When the meeting was over, Claire tried to leave, but her legs had tensed up again. She couldn’t conceal the crippled, rigid quality to her gait as she staggered towards the door. One of Claire’s friends caught up with her, and asked “Claire? Are you okay? Did something happen over the summer?”

Claire burst into tears. In between sobs, she tried to explain her strange stiffness, her anxiety, and the utter lack of medical insight.

She was ashamed to realize that other people could tell she was falling apart, and she was especially embarrassed that this particular friend would catch on. Claire’s friend was battling breast cancer, and Claire hated to think that her friend’s urgent needs would be subducted by her comparatively petty ones.

But in another sense, Claire’s friend was an ideal confidant. She was married to a doctor, and when she relayed Claire’s story to her husband, he referred Claire to a colleague at the Louisiana State University hospital. Claire made another appointment with another neurologist, got another EMG, and got the doctor’s verdict: She definitely had stiff person syndrome.

But the diagnosis didn’t give her a break from testing. The doctor ordered a blood test to check her levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies. The majority of patients with stiff person syndrome have levels that are unusually high, but not Claire. Once again, tests introduced more confusion than certainty.

![A photo of a large Starbucks coffe cup. On it, the barista (presumably named Milli) wrote in Sharpie, "Claire, i [heart] you! -Milli".](http://myuprightlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Thank-goodness-for-coffee-and-caring-baristas.-588x1024.jpg)

Stiffness, or a Stiff Person?

Although Claire’s diagnosis was frustratingly elusive, it came quicker than usual for someone with stiff person syndrome. The condition is poorly understood, and even well-trained, perceptive specialists have trouble diagnosing it accurately, for several reasons.

First, the condition is so rare that most doctors will never see a single case in their lives.

Second, the condition is relatively new to science. It was first identified in 1956, when researchers described fourteen patients with regular and prolonged muscle spasms. The condition was known as “stiff man syndrome” until 1991. However, the disorder occurs more frequently in women, and was eventually given a gender-neutral name.

Third, stiff person syndrome appears to be a spectrum of disorders rather than a single disease. But with so few cases, it’s difficult to tease out the subtypes, and establish firm diagnostic criteria.

There’s a considerable range of symptoms and presentations. For example, some patients will develop a rigid torso, and will have trouble bending, while others will only experience tension in their limbs. Most patients are in their forties when their symptoms set in, although children as young as seven have been diagnosed.

Although the underlying cause hasn’t been identified, stiff person syndrome appears to be an autoimmune disorder. Characteristic antibodies are often found in patients’ blood. Physicians have also noted its frequent association with other autoimmune conditions like Type I diabetes, pernicious anemia, and autoimmune thyroid disease.

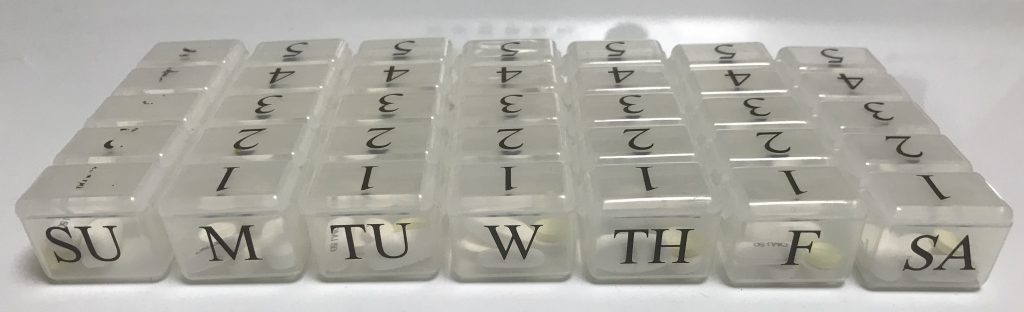

The peculiar symptoms appear to be due to a dearth of GABA, a neurotransmitter that stops nerve impulses. For this reason, people with stiff person syndrome are often put on crazy high doses of benzodiazepines (a class of drugs that include diazepam) and muscle relaxants (such as baclofen). These drugs act on nerves’ GABA receptors, and stop them from sending activation signals to muscles.

Treatment

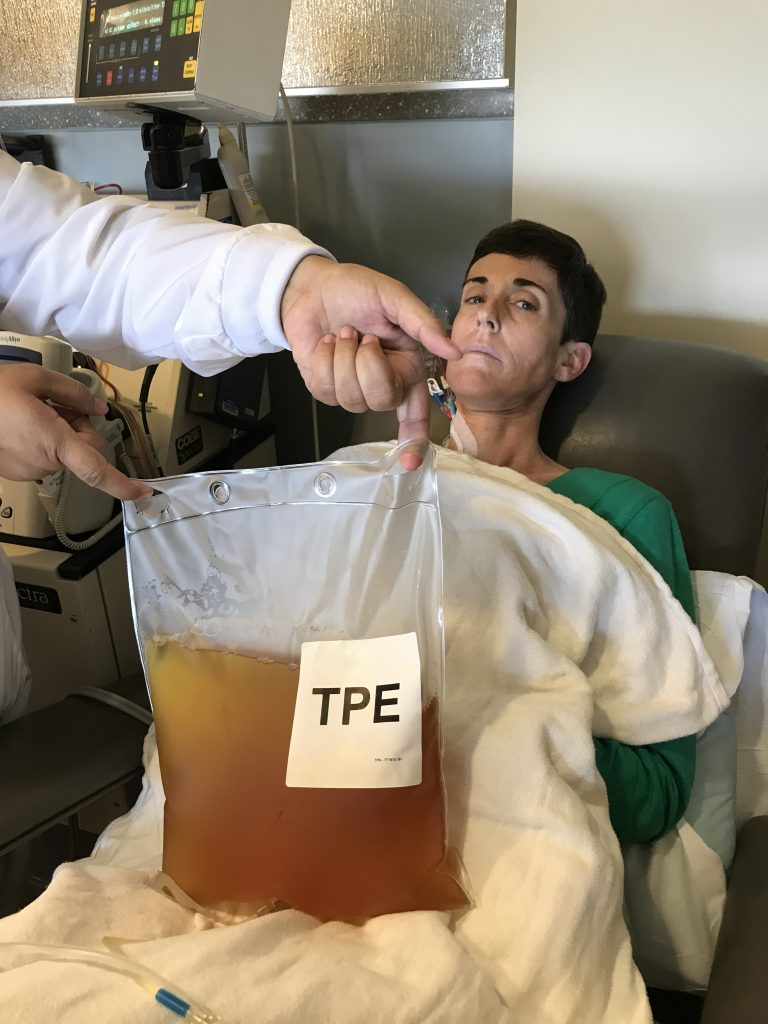

In January of 2016, Claire started a cocktail of medications, including benzodiazepines. She also signed up for a round of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), a treatment which involved giving her an IV drip containing healthy antibodies from other people’s plasma.

IVIG is frequently used to treat certain types of immune deficiencies, but it’s not without drawbacks. It’s costly, since a single round includes plasma from thousands of donors. And it’s time consuming. A fist-time patient is often injected with small amounts of immunoglobulins over two to three days in order to build up a tolerance. In Claire’s case, she was expected to get monthly boosters.

Claire did five rounds of IVIG without any noticeable effect. In May of 2016, she called it quits, and started relying exclusively on medication and alternative therapies.

Some of her doctors still questioned the stiff person syndrome diagnosis. Sick of the ambiguity, Claire flew to Rochester, Minnesota in March of 2017 to consult with experts at the Mayo Clinic.

If anyone could clear up the mystery, it would surely be the neurology specialists at Mayo. That was where the disease was first identified, and in the years since, the clinic had produced several other important breakthroughs.

The doctors at Mayo tested her blood and her spinal fluid, and gave her another EMG. Claire was coming to hate this procedure, since it involved forcing needles into her increasingly tense muscles.

She also had to undergo another test, which was uniquely torturous for someone with stiff person syndrome. The doctors hooked her up to electrodes, clipped an electrical device on her big toe, and gave her a pair of headphones in order to test her startle reflex. The headphones would occasionally blast a sound like a smoke alarm, and the device on her toe would deliver a jolt like a bee sting. The electrodes recorded Claire’s reaction.

Curiously, the doctors never examined Claire directly. They never asked her to undress, and they never placed a hand on her rock-hard muscles.

Even so, the specialists at Mayo found her test results conclusive. Claire had stiff person syndrome.

A Bad Year

Claire stumbled through 2017 with the help of medications and distractions. The movement neurologist in Louisiana didn’t believe the Mayo Clinic doctors any more than she had the rheumatologist. She still refused to believe Claire had stiff person syndrome, and wouldn’t prescribe the meds recommended by Mayo’s neurologists.

Claire felt alienated and alone. “If the doctor here won’t follow what Mayo wanted me to do, then what was the point of going?” she wondered.

Claire’s real life wasn’t going so well, either. She used to enjoy running and yard work, but her stiff muscles and unpredictable motion control made these everyday activities difficult. Besides, she had fallen twice, and didn’t want to make it thrice.

Instead, she would stay home and pace for hours, fixated on the possible disasters that unfurled in her mind. What if she couldn’t walk? What if she couldn’t help her special needs son with his physical therapy? What if she couldn’t cheer on her younger son’s robotic creations?

Mentally, she was willing to put her husband and children first. Physically, she couldn’t always control where she put herself. She didn’t trust herself to drive, so she put her kids on the bus in the morning, and hired strangers to help run errands. Was this the kind of mother she wanted to be? The kind of mother who had to hire someone to pick her kids up from school?

Her memory started to flit in an out, thanks to the high doses of Valium she took every day. She was becoming an unreliable narrator of her own daily existence.

If the thought was hard to choke down, it was nothing compared to actual food. She developed an aversion to certain textures and temperatures. Her throat muscles would clench, and she couldn’t swallow properly. “I started to not want to eat,” she said. “I was about ready to give up. I couldn’t imagine living in this amount of pain for the rest of my life.”

Claire, who stood 5’ 8” (173 cm), went from 138 to 113 pounds (63 to 51 kg) in a matter of months. When she started seeing a pain management doctor in January 2018, he didn’t congratulate her on her weight loss. “You’re dangerously thin,” he said. He prescribed a med to increase her appetite, and referred her to a gastroenterologist for an upper endoscopy.

The gastroenterologist wasn’t impressed either. “You don’t need an endoscopy,” he insisted. “You need a feeding tube.”

He scheduled the procedure, and everything that could go wrong, did.

A doctor surgically inserted a feeding tube in Claire’s stomach, but her muscles fought against it as best they could. “The stomach is a muscle, and it was trying to force the tube out of me,” Claire explained. “It pulsed, it throbbed. I couldn’t move, I couldn’t get dressed.”

She was sent to recover at home, and a nurse was assigned to check up on her. Claire spent her days lying on her right side, since the feeding tube didn’t permit her to lie on her left. The position was tolerable enough, until the nurse spotted a sunburn-bright patch of skin on Claire’s right thigh.

It didn’t look like anything out of the ordinary to Claire, but the nurse was concerned. She sent Claire to wound care, and the medical staff started probing the pressure ulcer. Then, Claire noted, “It erupted like a volcano.”

The wound was far more serious than it had looked, and it quickly became infected and refused to heal. By Mother’s Day weekend, Claire was running a fever of 104°F (40°C). She returned to the hospital, and an MRI revealed the underlying muscle was infected. She was put on antibiotics, and shipped to the ER, then admitted to the hospital where she would remain in isolation for ten days.

The doctors saw her list of medications, and freaked out. She was on a shockingly high dose of diazepam (Valium), and took other powerful, and highly addictive drugs. They assumed she was an addict (which she technically was, although not by choice), and stopped most of her medications.

Predictably, she went into withdrawal. Now, she also had to deal with sweating, headaches, and nausea, as well as worsening symptoms of stiff person syndrome. “It was horrible,” she said. “I didn’t know what withdrawal was like, and I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

To deliver a potent dose of antibiotics, the staff threaded a peripherally inserted central catheter up her arm. In the process, they nicked a major artery. Claire already had sepsis, and the blood loss nearly killed her.

Her original problem – extreme weight loss – had not improved over the last two months either. She was down to 109 pounds (49 kg).

While recounting this story, Claire observed, “It sounds like something that happened to somebody else. At the time, I didn’t know how sick I really was. My body was eating itself.”

After ten days, Claire was stabilized and released. But she wasn’t well, and recovery was a slow process. She spent the summer of 2018 doing gentle physical therapy at home and trying to regain her former function.

The Prince of Neurology

Once the crisis had passed, Claire returned to the pain management doctor who oversaw her care. In the fall of 2019, he referred Claire to a new doctor, a neurologist who had other patients with stiff person syndrome.

The new neurologist was familiar with Claire’s condition, but more importantly, he cared. “It makes a world of difference, when you’re used to being dismissed, and having doctors give up on you,” Claire said. “I had to kiss a lot of frogs to meet the prince of neurology. He’s caring. He’s kind. He’s not afraid to say, ‘I don’t know, but let me consult with so-and-so.’”

Claire’s history with the medical establishment was as troublesome as her history with her disease. All her tests and treatments had done little to make her better, and there was reason to think they’d made her worse.

“You reach a point where you’ve tried everything under the sun, and it’s discouraging when other people are getting better, and you aren’t,” said Claire. “You start to feel like your quality of life is nonexistent because you can’t leave your house, except for medical appointments. But my doctor assures me he’s never going to give up on me. He’s amazing. I don’t think I’d be as willing to continue treatment if I hadn’t met him.”

In February 2020, under the neurologist’s watchful eye, Claire started a new round of IVIG using a different brand of immunoglobulins. The first three rounds helped more than Claire anticipated, but the double whammy of COVID and pushback from her insurance company meant she had to delay further cycles and switch to a generic brand.

That Can Happen?

Claire’s disease changes, but it never stops. Some of her problems would be comical, if they weren’t so serious. She’s developed an exaggerated startle reflex. The rumble of a truck outside, or a flash of lightning seen through the skylight will cause her to jump, or fall backwards. Her husband changed the doorbell chime so it wouldn’t ring so loudly.

In 2019, Claire visited her old ear, nose, and throat doctor, who finally solved a longstanding mystery. The sensation of water in her ear was caused by a muscle going into spasm deep within her ear.

Last fall, she noticed her voice would take on a gravely pitch when she got stressed or tired. She learned this was caused by spasms in her vocal cords.

If she grips anything in her left hand for long, she can’t let it go. This is a special nuisance, since Claire is left-handed, and has trouble writing. Once, after driving in the rain, she had to physically peel her fingers off the steering wheel.

Her stiff muscles can be exceptionally painful. She gets Charley horses that wrap around her upper left thigh, which she calls “the python hug.” She also gets painful cramps in her ribcage, diaphragm, and abdomen. And when an already-clenched muscle decides to spasm…that hurts, no question.

As her condition progressed, Claire found herself developing another health issue, which was unique even among people with stiff person syndrome: she couldn’t sit down.

In 2017, before flying to the Mayo Clinic, Claire had a bout of anxiety before the plane ride. But this time, she wasn’t afraid of sensory overload. She was terrified that sitting would cause her pain.

She would eventually be proven right. Over time, Claire developed spasms in her tailbone and low back that were aggravated by sitting. Sometimes, it felt like there was a fire in her butt. Once the muscle spasms in her sacrum started, sitting on her behind only caused more pain. Ice and heat only caused her excitable muscles to contract with greater intensity.

A Thirty-Minute Pity Party

Stiff person syndrome progresses in fits and starts, and Claire is not at all certain what the future holds. Although she tries to keep a cool head, sometimes the fear, and uncertainty, and sadness boil over. She can’t prevent It, but with the help of her therapist, Claire found a tolerable way to deal with those moments.

“I do a self-check,” she said. “I tell myself, ‘You can do a thirty-minute pity party, and then you have to go fold laundry.’ I’ve tried the wallowing, but it’s not good for my family, and it’s not good for me.”

Although Claire knows the illness isn’t her fault, she sometimes feels guilty about letting her own needs supersede the needs of others. A few months ago, her oldest son had surgery to reconstruct his misshapen food. Claire waited in the hospital while the surgeon was working, and agreed to help with her son’s physical therapy afterwards. But the fourteen-hour ordeal was taxing, and she felt guilty knowing that her own therapy needs would take priority over her son’s.

“Time has dragged by at times, but at others, I wake up with a sixteen-year-old and an eighteen-year-old, and I feel like I’ve missed a huge chunk of that,’ Claire said. “It’s hard not to feel selfish.”

Her husband and children, at least, are no small comfort. Despite living through their own struggles, both her boys are growing up to be self-sufficient young men. Claire’s oldest son graduated high school with honors, and was accepted into a combined work and study program. Claire’s youngest loves building robots, and is contemplating a career in chemical engineering.

When Claire is in need of encouragement, she draws an index card from her collection. She wrote an inspiring quotation on each. One of her favorites comes from the writer and artist Mary Ann Radmacher. “Courage doesn’t always roar. Sometimes courage is the little voice at the end of the day that says I’ll try again tomorrow.”

Hi Lisa,

I expect you have joined support groups for SPS. I am the founder of the UK & Ireland website and closed fb page. If you would like to join. please click on the ‘F’ on the website. You will be asked 3 questions and once answered I can add you. (We are registered with the charity commision as SMS as that’s what it was called when I was diagnosed.

Hi Claire,

I expect you have joined support groups for SPS. I am the founder of the UK & Ireland website and closed fb page. If you would like to join. please click on the ‘F’ on the website. You will be asked 3 questions and once answered I can add you. (We are registered with the charity commision as SMS as that’s what it was called when I was diagnosed.

Hi Claire,

So sorry for all that you have been through and are going through. I can relate. I have SPS and two teens! Symptom onset beginning of 2015, diagnosed in 2017 after running from doctor to doctor panicked. I started a foundation to help raise awareness and money for research. Just donated 40K to Hopkins. Would love to connect!

Tara Zier

http://www.stiffperson.org

tara.zier@gmail.com