While I’m skeptical of chairs in general, I’ve heard several people with back pain or sitting pain say they get relief by sitting in zero-gravity chairs. I didn’t know what these were, but they sounded cool and I was certainly interested in finding a usable chair, so I started poking around.

This research project soon led me in unexpected and interesting directions, as I found myself combing through NASA standards, papers from the 1970s, car commercials, and reports of the weird things space does to your body.

I learned to separate the marketing claims from the actual research upon which they were based, and determine which “benefits” were actually worth getting.

Full Disclosure: I don’t have a zero-gravity chair, nor (knowing what I now know) do I intend to get one. But if you have one or plan to get one, fear not. The worst danger that is likely to befall you is that you’ll overpay for something you end up not liking.

What is a Zero-Gravity Chair?

While there’s a lot of variation among zero-gravity chairs, in general, they’re designed to support your entire body as you lay back. Many zero-gravity chairs function like recliners, in that they allow you to adjust them into several positions.

They range from inexpensive, folding lawn chairs to deluxe massage chairs that are destined to stay wherever the delivery person put them.

Manufacturers and retailers often tout their supposed health benefits, which range from muscle relaxation, to enhanced circulation, to back pain relief. Another frequent claim is that these chairs were influenced by NASA, although the details are rarely given.

Skylab: NASA Discovers Neutral Body Posture

The story of the zero-gravity chair begins, as so many American technology stories do, with the space program.

The earliest space craft (such as the Apollo capsules I recognize from repeated viewings of Apollo 13) were designed with Earthly constraints in mind. But as people spent more time in space, it became obvious to scientists and the astronauts themselves that bodies in microgravity behave differently than bodies on the ground.

Astronauts’ spines lengthened, and the curves flattened. They sat taller, since (in additional to their spinal changes) there was less pressure on their butts and heels. Fluids were redistributed through the body, which led to thinner legs and puffier faces.

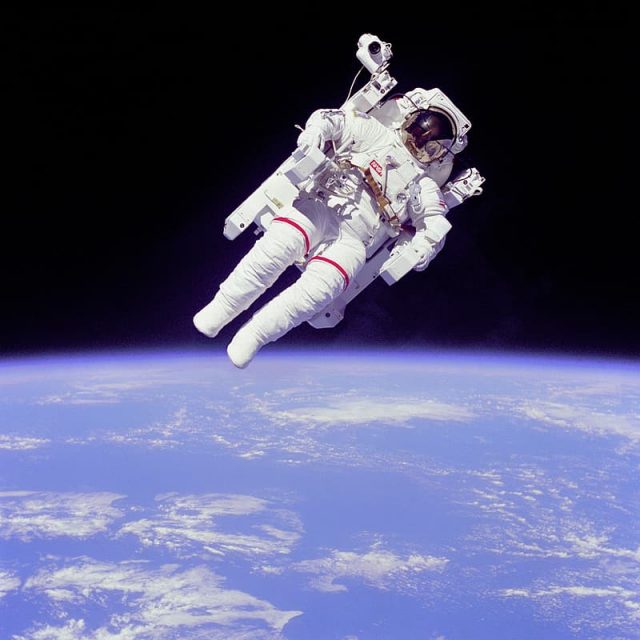

One thing that scientists noticed was that people assumed a different posture when they were floating around, free from the constraints of gravity. They didn’t really sit or stand. Instead, they sort of hovered in a relaxed curve.

Naturally, NASA did some experiments on astronauts to measure their exact position, and published a paper on the topic in 1978. They later included these measurements in standards that specified how spacecraft should be designed to accommodate people.

It should be noted that the original experiment was performed on 12 astronauts, all of whom were young-to-middle aged, reasonably fit, white men. This selection was entirely pragmatic, considering that the resulting measurements were intended to accommodate other astronauts who would presumably have similar demographics.

New Data Casts Doubt on Neutral Body Posture

A particularly influential critic of the original study was the European Space Agency (ESA). They complained that the sample size was too small, and measurements weren’t accurately taken because the astronaut’s clothes obscured their bodies. An ESA review of the initial data showed that astronauts only maintained their supposed neutral body posture in 36% of the photos and videos examined.

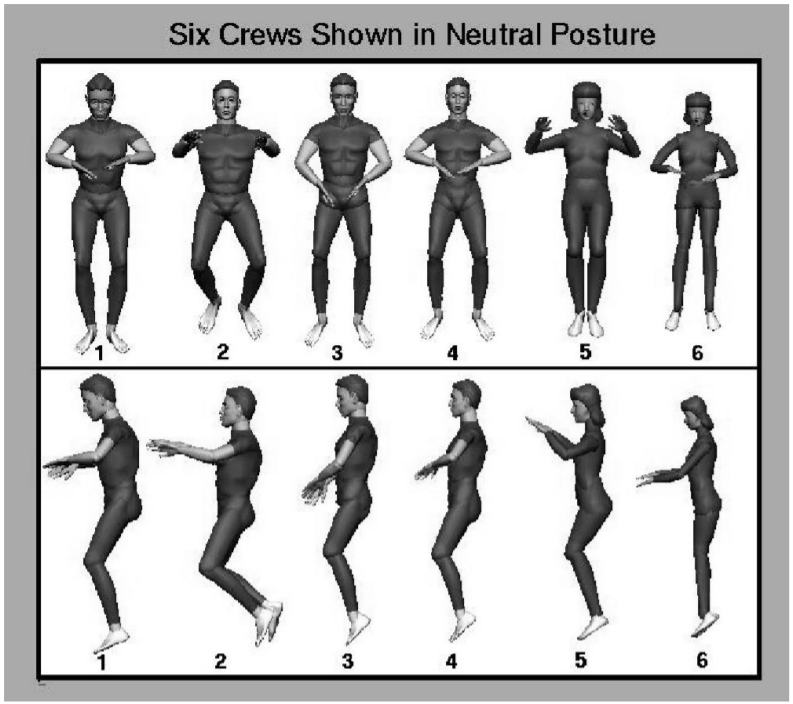

They had a point, and NASA seemed to agree. In 2003, NASA published an updated report with data from six crew members on the Endeavour.

Although there were only six subjects in the new study, the approach was more rigorous. The astronauts were thoroughly measured on the ground, and were given shorts and tank tops to wear when the images were being recorded. They were instructed to assume a relaxed postured that wasn’t oriented to any particular task, and to wear sleep masks while the data was being collected.

This time, the subjects included two women, and the crew members’ sizes were more spread out. One petite woman was only 151.6 cm (5 ft) tall, and weighed 45.8 kg (101 lbs.). The largest man was 183.6 cm (6 ft) tall and weighed 82.1 kg (181 lbs.).

The published study noted that, “No single crew member exhibited the typical NBP called out in the MSIS.” Moreover, the six astronauts studied had postures that were significantly different from each other. One woman almost appeared to be standing upright, while one man posed like he had just jumped off a trampoline.

The paper concluded that, “The data also indicated that several postures were evidenced in microgravity, thereby providing a range of postures that may be more representative than the single, all-encompassing posture documented in the MSIS. This suggests that the MSIS was generalized significantly and should be updated with additional data points to provide more representative crew postures.”

Other Industries Discover Neutral Body Posture

Long before the new results were published, engineers in other industries were drawn to the idea of a natural posture that humans assumed when gravity wasn’t a factor. Any concerns about data quality were easily brushed aside, and the concept of neutral body posture was quickly adopted and adapted for terrestrial use.

In 1985, a grad student at Texas Tech took it upon himself to design a more comfortable chair based on neutral body posture. In a subsequent study comparing the comfort of this chair to an existing model used by surgeons, the neutral body posture chair was determined to be significantly more comfortable.

Shortly afterwards, the data also influenced the design of a new seat for industrial sewing, and 2018, researchers drew on the data to redesign an MRI chair.

The general public might have remained entirely unaware of this obscure concept if it wasn’t for Nissan. In the mid-aughts, their engineers were tasked with designing a more comfortable seat, and they decided to use neutral body posture as a starting point.

They did some modeling, built a prototype, and even published a paper with the results of their tests. Their paper wouldn’t win any awards for methodological soundness – one key experiment involved having four young men sit in one of three seats for two hours, and report on their discomfort. (Like the first astronaut subjects, all the subjects used in Nissan’s first experiments were young men.)

I’m not the world’s most qualified chair judge, but I noticed the standard seat model used for comparison looked particularly uncomfortable. So, while Nissan’s results showed the neutral body posture seats to be more comfortable, I’m not sure that’s saying much.

Anyway, Nissan debuted their new astronaut-inspired seat in the 2013 Altima. Perhaps no one was more enthusiastic about it than Nissan’s marketing team. They produced a video with floating astronauts and animated blue wireframes, and their blog includes catchy phrases like, “[W]hile other cars have seats, Nissan has science.”

Perhaps We Should Call Them 3G Chairs?

Confusingly, some zero-gravity chair manufacturers claim their chairs are based on the ones that astronauts are strapped into during takeoff and landing. In that case, “3G chair” might be a more accurate label, since astronauts are certainly not experiencing zero gravity during a shuttle launch or reentry.

I’m not sure where this claim originated, but I’m pretty sure that no one consulted NASA. Photos from the space shuttles and Soyuz capsule (currently used to bring astronauts to and from the space station) show astronauts crammed into a folded-up position. They don’t look much like the commercial chairs meant for long-term lounging.

There is one sense in which astronauts’ postures resemble those of Earth-bound chair users. Astronauts do lay on their backs during launch and reentry, since that position helps their bodies absorb G forces. If they sat upright, fluids would be pushed down into their feet.

When designing seats, NASA engineers are more concerned with safety and utility than comfort. They worry that astronauts might hurt themselves or damage sensitive equipment if they’re knocked about during a launch. An injury could be a serious problem if the astronaut is going to be stuck in space for a while.

It doesn’t help that astronauts are prone to getting dizzy, especially on reentry. This is due to a condition called orthostatic hypotension. People on Earth get orthostatic hypotension too; if you’ve ever gotten fuzzy vision after standing up too fast, you know the sensation.

Engineers use several methods to pack people up like cargo. Soyuz seats are custom-molded to an astronaut’s body, so the person fits like a Styrofoam-packed ceramic figurine. Astronauts are also strapped in tightly by support crew members before launch. They wear spacesuits in case something goes wrong.

Designers of zero-gravity chairs are trying to solve a different set of problems, so their chairs turn out differently as well.

Are Zero-Gravity Chairs Good for Your Health?

When you think about it, it’s weird that the adjective “zero-gravity” would be applied to anything that’s supposed to be good for you. Weightlessness provides no health benefits to astronauts. On the contrary, they regularly experience nausea, distorted vision, changes in muscle fiber type, atrophy of the heart, and rapid loss of bone and muscle mass.

But, I dunno, maybe simulated weightlessness here on Earth is a good thing?

Spine Benefits of Zero-Gravity Chairs

Some zero-gravity chair manufacturers claim that their chairs “decompress,” “rehydrate,” or “reduce pressure” on your spine. This is sort of true, although whether that will actually help you is debatable.

When you’re walking around during the day, the pressures exerted by your own bodyweight and gravity force water out of your discs. When that pressure is reduced, your discs soak up water again. This happens every night when you lie down to sleep, and it explains why people are taller in the morning than they are in the evening.

It makes intuitive sense to think that fully hydrated discs are healthier. After all, isn’t dehydration a bad thing? But that assumption is too simplistic. While I wouldn’t frame either state (hydrated or dehydrated) as good or bad, having fully hydrated discs can predispose people to certain types of injuries. This is because, when the discs are swollen with water, the ligaments are stretched and the spine isn’t as flexible.

In Low Back Disorders, McGill writes (page 131), “Adams and colleagues estimated that disc-bending stresses were increased by 300% and ligament stresses by 80% in the morning compared to the evening; they concluded that there is an increased risk of injury to these tissues during bending forward early in the morning.”

Lying in a zero-gravity chair for an extended period of time is likely to “decompress” your spine and “rehydrate” your discs, but lying on a normal couch or bed would accomplish the same thing. And there’s no obvious reason why these changes should improve your overall health.

Cardiovascular Benefits of Zero-Gravity Chairs

Claims that zero-gravity chairs improve circulation do have some merit, but the benefit comes from raising the legs over the level of the heart. (Not all zero-gravity chairs are designed to do this.)

People who have conditions that cause blood to pool in the legs (such as edema, varicose veins, and chronic venous disease) may benefit from elevating their legs. That position encourages blood to keep flowing, and can reduce swelling.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for the European Society for Vascular Surgery note that, “Leg elevation has been used for a long time and is still recommended to patients to ameliorate venous stasis, provide symptomatic relief, reduce leg oedema, and promote healing of ulcers in patients with CVD.” (Note: CVD = Chronic Venous Disease.)

Of course, a zero-gravity chair isn’t the only way to get those benefits. Patients can accomplish the same thing by stacking pillows under their legs while they lay on their backs.

Conclusion: Should You Get a Zero-Gravity Chair?

I’ve spent most of this article patiently picking apart the claims made by zero-gravity chair manufacturers. The astronaut comparisons are absurd, and from a health perspective, a recliner, couch, or bed, is likely to be just as beneficial.

But while most of the claims made by peddlers of zero-gravity chairs are baseless (or at least overhyped), the chairs themselves aren’t uniquely dangerous. They’re just…chairs.

If you view “zero-gravity” as just another chair descriptor, like “wingback,” “papasan,” “rocking,” and “ladderback,” and you like the style, then I won’t dissuade you from getting one.

My husband and I didn’t look at a single academic study before we bought his La-Z-Boy recliner. We just went to the store, and sat in them. We bought the one he found most comfortable.

If you insist on getting the astronaut experience, wait until just before an earthquake. Then, tip a sturdy chair on its back inside a closet, and have a brawny friend strap you onto it. Wait several hours. If you can get a line of cement mixers to drive around your place while this is happening, so much the better. Ask your burly friend to lie on top of you for the full G-force experience.

Zero-gravity chairs sound awfully comfortable in comparison.

I think the reclining position and weightlessness help to reduce back pain. but I don’t think It can help overnight! maybe it need months!