Recently, I boarded a train of thought that stopped – as many trains of thought do – at sciatica.

It began with me watching Pose, and thinking of the cinematic suffering of the characters with AIDS, then listening to Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, and AIDS and Its Metaphors, and finally, comparing cancer and AIDS to back problems.

Do you know of any books, TV shows, or movies, where a character’s back problems are a significant focus? Or even a distinct part of their identity? I could recall a few scenes where an incident of acute back pain was played for comic effect, like when Jerry Seinfeld’s back outlasted an entire male line. But serious back pain that didn’t resolve itself over the course of the episode? I drew a blank.

In literature, I couldn’t recall a single example of a book where back problems were more than just a throw-away line. After some frustrating Googling, I figured that either examples really were lacking, or I selected terrible keywords. I didn’t even bother searching for “sitting disabilities.”

This absence is notable, considering the World Health Organization puts the lifetime prevalence of low back pain at 60-70%.

Are There Good Diseases for Literature?

In How to Read Literature Like a Professor, by Thomas C. Foster, the author points out that some diseases lend themselves to literary interpretation better than others.

He points out that in the late 1800s, cholera and tuberculosis were about equally common, and syphilis and gonorrhea reached epidemic proportions. Yet, in literature, tuberculosis (also known as “consumption”) was by far the most popular disease.

Why? Foster lists three factors that give a disease strong literary potential.

- It should be picturesque. Remember Moulin Rouge? In the movie, the beautiful Satine delicately coughs blood onto a handkerchief, and faints while belting out a Madonna cover on a trapeze. The vomiting and diarrhea that are characteristic of cholera don’t play as well on camera.

- It should be mysterious in origin. There’s nothing particularly mysterious about a smoker who dies of lung cancer, and it’s hard to kill off a character in this way without sounding like a public health announcement. The few writers who specifically write about lung cancer tend to do so out of personal experience. (Examples include John Updike and Raymond Carver, both of whom died from the disease.)

- It should have strong symbolic or metaphorical possibilities. Tuberculosis was a wasting disease, and a great way to show a young life cut short. Today, cancer can serve the same purpose. Malaria translates to “bad air,” and was an appropriate way for Henry James to kill off Daisy Miller. Heart disease could be a manifestation of so many character defects.

I would add another pair of items to Foster’s list – a good literary disease should be fatal (or at least potentially fatal), and it should kill off the young. A 75-year-old hospitalized for pneumonia doesn’t have the same dramatic oomph as a teenager wasting away on chemo.

To bring this back to Pose (which, in case you’ve forgotten, was the inspiration for this post), AIDS is also an appropriately literary disease. I didn’t have any trouble thinking of examples from the stage (Rent, Angels in America), screen (The Hours, Philadelphia) or page (The Way We Live Now, Push).

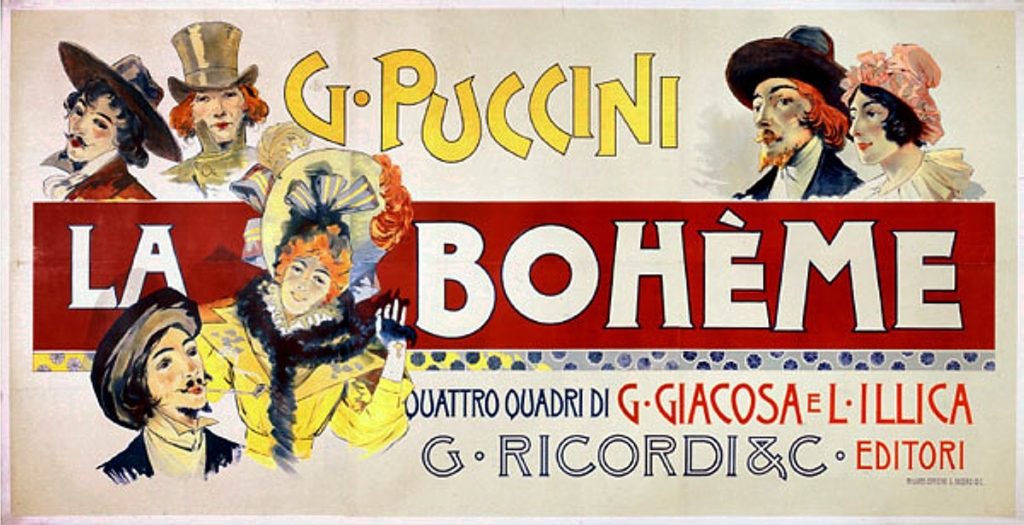

The literary kinship of AIDS and tuberculosis was especially apparent in Rent because the creator directly swapped out diseases from the opera, La Boheme.

Is Back Pain a Bad Disease for Literature?

So it would seem.

True, it’s often mysterious in origin (to the general public at least), but it doesn’t check the other literary potential boxes. Back pain isn’t visible from the outside, so it’s not picturesque. Nobody dies from it. Nor is there an obvious irony or metaphor to play around with. (E.g., a blind character who sees what no one else can, or a professor with schizophrenia.)

While bad colds and the flu can serve to further the plot by putting a character temporarily out of commission, back pain doesn’t offer such a predictable trajectory.

Even though back pain can strike at any age, it is commonly thought of as an affliction of the elderly. Even medical professionals carry this misconception. I’ve had several doctors tell me that I’m too young to have my life destroyed by back pain. (Which leads me to wonder, what is the magical age limit when it becomes acceptable to have one’s life destroyed by back pain?)

The military metaphors that are called into action for cancer and infectious diseases seem inappropriate when it comes to back pain. Would you call someone who bends over to tie their shoe and ends up herniating a disk a “warrior”? Am I really a sciatica “survivor”?

In some cases, an overreliance on these metaphors can make a bad situation worse. It’s ridiculous to tell someone who is crippled by a damaged end plate, “You have to keep fighting! Don’t let this thing beat you!” (Since this kind of damage is often caused by excessive compression on the spine, this sort of attitude could actually be harmful.)

It’s a heck of a lot easier to find illustrations for tuberculosis than back pain.

How to Use Back Pain as Metaphor

Naturally, I started thinking about how back pain might be used to good effect in stories.

Back pain is not a public affliction. Not only is the suffering invisible, but individuals in the throes of a serious episode are not going to be out doing a lot of socializing. It’s the sort of condition that generates a magnetic pull towards the couch.

This limitation means that if back pain is going to serve a literary purpose besides plot convenience, it should be restricted to the protagonist or one of the main characters. It’s too easy for back pain to flit out of sight if it belongs to someone at the periphery of the protagonist’s world.

Possible dramatic uses of back pain include:

- As a companion condition to a troubled and secret backstory. Both conditions would be a private torment. For example, an army veteran who is haunted by his actions in a past war also suffers regular, crippling back pain.

- As a symbol of a consuming ideology. For example, a young revolutionary devotes every waking moment to overthrowing capitalism. Sciatica tortures him physically, wakes him from his sleep, and compels him to soldier on past the point of total exhaustion.

- As a way to call the narrator’s reliability into question. I am all too aware that doctors have no objective way to quantify back pain, and must rely on a patient’s report. In real life, this means patients’ veracity is often called into question, and sufferers can be accused of exaggerating or malingering. This drives me nuts, but I can see the literary potential. By writing an unreliable narrator who frequently complains of back pain, an author would invite readers to play a game of Real or Not Real?

- As an ironic limitation on a physically powerful character. For example, a powerlifting champion who relies on his wife to lift the laundry basket, or a football coach who can’t pull on his socks in the morning.

Perhaps there’s even a place for back pain in fairy tales.

Once upon a time, there lived a dragon with a bad back. He offered his entire hoard of gold to anyone who could offer a cure. Many wise men and women offered potions, and talismans, and incantations, but none worked. Now the dragon had a collection of crystal bottles and precious stones, and indigestion from all the wizards and crones…

One thought on “Back Pain as Metaphor”