As a little girl, Lisa didn’t want a pony. She had one. She wanted her brother’s minibike, never mind that it was broken.

Her brother agreed to the trade, no doubt thinking that a running Shetland was better than a broken scooter. Within an hour, Lisa had replaced the faulty spark plug, and could run circles around her brother and his pet.

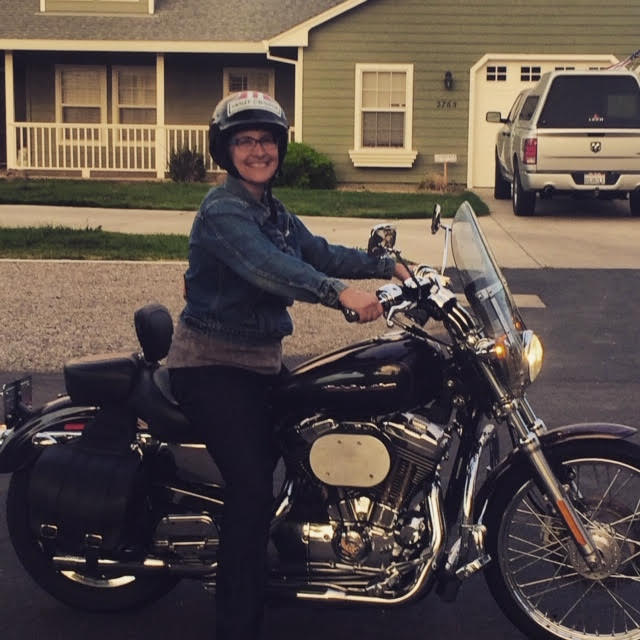

Lisa’s love affair with engines and fast rides would remain with her for decades. And no one, certainly not Lisa, expected that a little thing like nerve entrapment would pull her permanently off a motorcycle.

Off to a Rough Start

Lisa was never the sort of woman to do something just because it was expected. In high school, the only class she got excited about was small engine repair. This was in the late 1970s, and the administrator at the regional occupational center where the classes were held was perplexed – wouldn’t Lisa prefer to take home ec instead? No, she wanted small engine repair. And she insisted they install a women’s bathroom in the center.

The center agreed, and soon, Lisa was showing the boys how to change oil, and repair a four-barrel carburetor. But she would only finish out half the year before she crashed her motorcycle, and ended up with a concussion, a collapsed lung, a broken arm, a separated shoulder, and serious burns. She stayed out of school for a semester while she recovered.

By age fourteen, Lisa was already used to trauma. As a small child, she was sexually abused by her paternal grandparents. At age twelve, she was hitchhiking with a friend when a stranger kidnapped the two girls, and spent three days raping them repeatedly in the middle of an empty quarry.

After Lisa was finally released, and hitchhiked back home, her mom chose to believe her story that she’d gone on an unexpected camping trip. It was either that, or call the cops, and Lisa’s mother harbored a deep distrust of the police ever since they tore her house apart on a drug bust.

Safe to say, Lisa’s view of relationships and sexuality were skewed, an issue that would plague her for the rest of her life. At age sixteen, she married her first husband. Two years later, the relationship ended after he grabbed Lisa by the hair and threw her into the wall while she was holding their infant daughter. Lisa waited until he left for the weekend, sold their possessions, and ran to a shelter. She never looked back.

Her next relationship produced two children, but Lisa left once she realized her boyfriend’s meth habit wasn’t going to resolve itself.

Given the drama of Lisa’s young life, it’s no surprise that her real life took priority over her studies. She dropped out of high school, and spent the next twenty years changing oil and holding low-paid jobs while she cycled in and out of toxic relationships.

Course Corrections

Many parents convince their children to go to college. In Lisa’s case, it was the other way around. Her second daughter, Tressa, decided to start junior college in 1999, and the pair made it a mother-daughter experience. Tressa soon outpaced her mother, and transferred to another school after three semesters. Lisa spent her days changing oil, and her nights studying.

It took Lisa three years to earn a two-year liberal arts degree, but in 2001, she graduated, and went on to purse a bachelor of arts in criminal justice and corrections.

After earning her BA in 2005, Lisa got a job as a group supervisor in juvenile hall. She learned two things about herself. First, she liked working with teenagers. Second, she was good at it. Within a year, she was promoted, and became a probation officer.

She found a way to make herself useful by handling the probation paperwork for both adult and juvenile cases. Most of her coworkers despised writing endless reports, but Lisa liked the investigative work that went into them, and she liked making recommendations that held sway in the court.

The work involved interviewing murderers, thieves, and rapists, as well as their victims. Lisa would try to put the crimes in context by looking into the perpetrator’s history and circumstances. She would also consider whether the defendant showed remorse, and whether they were likely to reoffend. She described her role as, “part lawyer, part psychologist, but mostly social worker.”

Once she finished her report, she submitted her sentencing recommendation to the judge, who had the ultimate decision-making power.

“I had a lot to relate to with teenagers,” Lisa explained. “Some of them committed crimes because their home lives were shitty. Some had parents who were molesting them, stuff like that. If it was relevant, I’d include that in the report. I could triage them to treatment.”

She also had a stint as a truancy officer, where her approach was to work with both families and schools to uncover sources of simmering resentment, and find solutions that would cool tempers.

Her hard work did not go unrecognized. In 2010, while working on her master’s degree in justice management, Lisa won the Probation Officer of the Year Award for the Sacramento region.

In 2012, after she finished her online master’s degree, Lisa transferred to nearby Sutter County, where she would remain until her retirement.

Sports Cycle

Although Lisa spent most of her time working on motorized vehicles, she loved anything with wheels. She was a dedicated skateboarder until she got too old to be seen hanging around skate parks. She decided to take up a hobby that was suitable for mature women. Like, roller derby.

Roller derby turned out to be a perfect fit for Lisa, who liked to alternate between speed and collisions. But at 47, Lisa was the oldest player on the team, and an injury was only a matter of time. During one practice, Lisa crashed, and strained her medial collateral ligament (a band of connective tissue on the inside of her knee). This injury put her at risk of hyperextending the knee, and once again, Lisa was forced to switch pastimes.

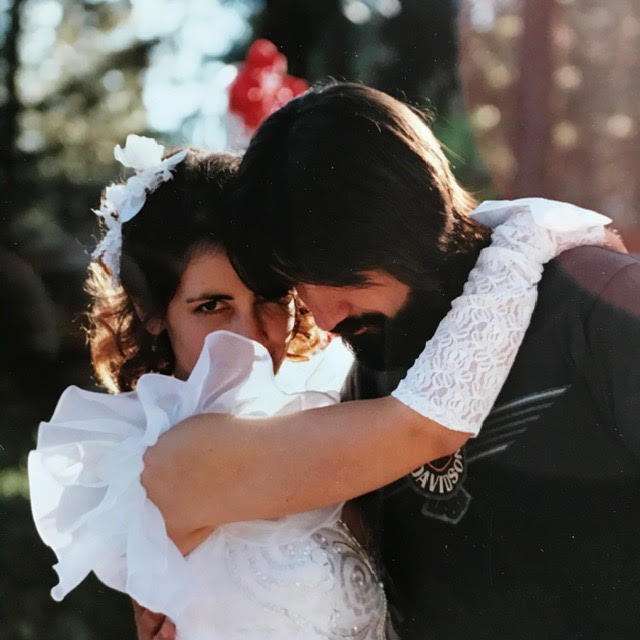

Luckily, she had another burgeoning passion. Lisa’s fourth husband was an avid cyclist, and she had caught the bug. Soon after the couple married in 2005, they got matching mountain bikes and started hitting the trails.

On a typical day, Lisa would spend a half hour on a stationary bike before jumping on her real bike and pedaling the five miles to work. On the weekends, she and her husband would regularly bike sixty miles.

Lisa needed more of a challenge, so she started cross-training. She started hot yoga and running, and eventually worked her way up to a half-marathon. She took up swimming, thought what the heck? And decided to compete in triathlons.

Lisa’s husband was a fitness buff himself, and encouraged her exercise habit. But sometimes his encouragement crossed the line into bullying. If Lisa’s weight rose above her typical 150 pounds (68 kg), he would make derisive comments, and pick on every perceived flaw, until she was shamed into dropping the extra weight.

Two Bad Rides

In 2010, Lisa signed up for a triathlon. The participants started with a half-mile swim, then ran up a hill to fetch their bikes for the 13 miles ride back down. They would finish by running a 5k.

The first leg of the race went swimmingly, literally. Lisa ran up and got her bike, then raced down the hill at top speed.

But there was a problem. Although it was a clear day, there had been rain a few days ago, and a dip in the road held a puddle. Lisa flew around a curve and saw it, but she was going too fast to stop or slow down in time. She saw her options a split second before she had to choose. She could either veer to the left and slam into the guardrail, or veer to the right, and crash into the forested hill.

She went right. Her bike toppled over, and Lisa skidded on her right arm, earning a considerable number of scrapes in the process. Her head hit the pavement hard enough to crack her helmet. She rebounded, smacked her shoulder against a tree, and flew over the left side of the road anyway.

She went crashing down what was, essentially, a cliff. She crashed down fifty feet, the bike pedal still stuck to her foot. At least the wait for help felt shorter than it was, since Lisa had passed out.

Fortunately, a cyclist riding behind Lisa had seen the accident, and called for a medic. Once the medic found Lisa and made sure her neck wasn’t broken, he still had to take her to safety. She regained her senses well enough to hitch a ride on his motorcycle, and go to a waiting ambulance.

When they arrived at the ambulance, Lisa showed her impressive collection of scrapes and bruises to the EMT, who happened to be an old friend of Lisa’s from her roller derby days. The entire right side of Lisa’s face was turning black, and both women had to admit that Lisa was in tough shape, even by roller derby standards.

Lisa took a trip to the emergency room, where the doctors were mostly concerned about her injured shoulder and the contusion on her head.

Shortly after she went home, Lisa started to notice another, more subtle sign of damage. She could feel a buzzing sensation near her cervix, and sometimes half her crotch would go numb. Days and weeks passed, but the sensation didn’t go away. Lisa would have to be careful when she sat at work, because she’d often lose feeling in her left leg.

For five years, these sensations seemed like a minor curiosity. They were weird, but not painful or particularly unpleasant. And Lisa could deal with the numbness.

Then, one day in 2015, Lisa’s husband suggested they try out a tandem bike. A couple he knew had one they could borrow for a few hours. Why not give it a go?

Why not, indeed. When Lisa and her husband got the bike, she hopped onto the back seat. The bike’s owner was clearly not the same height or shape as Lisa, and Lisa found the existing configuration uncomfortable. The seat was up too high, and her backside didn’t fit well on it. Lisa’s husband suggested they head out anyway. The bike alignment might not be perfect, but he was confident she wouldn’t find it unmanageable during their short ride.

He was wrong. Lisa was hit with excruciating pain almost immediately. Before they had gone a mile, she realized she wasn’t about to tough this one out. She begged her husband to let her go back. She would happily have walked the extra mile, but he convinced her to pedal back instead.

The Cyclist’s Syndrome

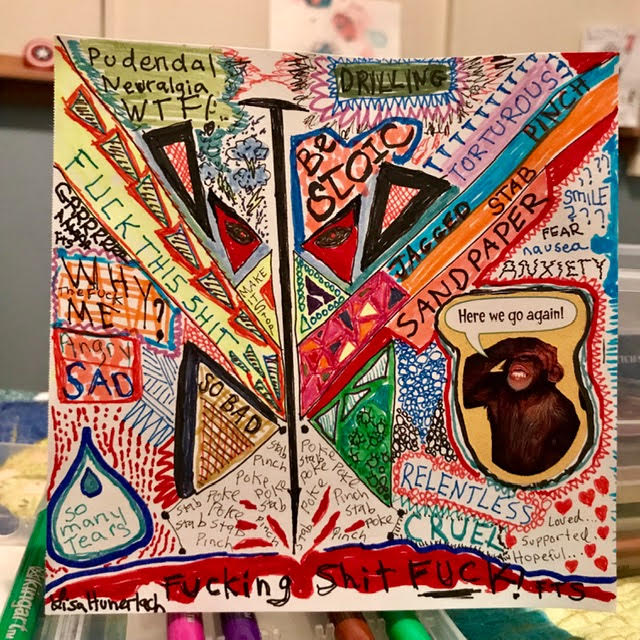

Lisa hoped her pain would improve once she got away from the wretchedly uncomfortable tandem bike. But it didn’t. The sensations inside her vagina were horrible – she constantly felt like she was being stabbed, pinched, and burned.

She couldn’t be sure what was happening, but she remembered an article she’d come across in a cycling magazine about a so-called cyclist’s syndrome. The symptoms seemed to match hers.

The medical name for cyclist’s syndrome was pudendal neuralgia, but the nickname was fitting. Pudendal neuralgia has been associated with cycling since it was first identified as a discrete condition in 1987. French researchers noticed that cyclists reported a set of symptoms which appeared to be due to the compression of the pudendal nerve in the pelvis.

The current diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia include pain in the area from the anus to the clitoris (in women), or the anus to the penis (in men). Pain is usually lowest in the morning, and gets progressively worse throughout the day. Sitting is painful; standing and lying down are better. Many sufferers report feeling like they have something shoved up their butt (spouses are quick to affirm) or their vagina.

In Lisa’s case, only the nerve branches that went to the clitoris and perineum were affected. She was spared the rectal symptoms that many sufferers develop, although the pressure in her colon before a bowel movement still spiked her nerve and muscle pain.

While pain is the most unpleasant symptom of pudendal neuralgia, function is often affected as well. Lisa had trouble detecting when her bladder was full, and learned to set a timer so she could remember to pee.

Lisa’s first stop on her search for help was her gynecologist’s office. Lisa brought up pudendal neuralgia, and asked whether it might be responsible for her symptoms. But her gynecologist was doubtful, noting that, “It’s so rare, it’s not even worth considering.”

The gynecologist thought that Lisa’s fibroids were the more likely culprit, and proposed a hysterectomy to take care of them. Since Lisa was fifty-four and post-menopausal, the gynecologist suggested they take her ovaries too. That way, they could control the amount of estrogen Lisa had in her system.

If Lisa had any doubts, she swallowed them, and deferred to her doctor. After all, her gynecologist had decades of medical training and experience. Surely, he knew what was best.

The Hysterectomy Doesn’t Work, and Neither Can Lisa

In 2016, Lisa underwent a hysterectomy and oophorectomy. She was now minus one uterus and two ovaries, but her pain was as sharp as ever.

She also faced uncomfortable choices in her professional life. Lisa had been out of work on temporary disability while she followed the gynecologist’s treatment plan, and hoped she could return after the operation. It was now clear that her problems wouldn’t be so easily resolved, and she needed to make permanent arrangements.

Returning to work was a physical impossibility. Driving there was torture, and Lisa couldn’t focus on her job when she felt like she was sitting on a hot poker.

Seeing no better options, Lisa officially retired on March 1st, 2017, but her departure was more bitter than sweet. It seemed desperately unfair – she had worked in low-paying jobs for twenty years before she found a career she enjoyed and that she was good at. Now that she was finally making professional progress, she was forced to quit. But pain is a powerful motivator, and Lisa knew her health needed to come first.

In mid-2018, when it was clear Lisa wasn’t getting better anytime soon, she applied for disability. Her familiarity with the legal system proved advantageous, and her application was accepted on her first try.

A Painful Separation

Her pain would cost Lisa more than her job. Her husband quickly grew frustrated with the new status quo. He privately (and publicly), thought that Lisa was exaggerating her pain, and she ought to take a more stoic approach. He was quick to point out that they were still paying off her college loans, and she needed to make a financial contribution to the household.

Cycling had also lost its appeal for Lisa. Her husband sorely missed her company on their road trips. He also disapproved of the weight she was rapidly gaining now that she couldn’t exercise.

Finally, Lisa’s condition put a serious crimp in their love life. If Lisa became aroused, she would be alerted to the change by the waves of burning pain that swept through her clitoris. Actual orgasms left her in tears, and not in a fun way. She avoided sexy movies. She avoided TV in general, lest an unanticipated romantic scene sent her scrambling for an ice pack.

As far as Lisa was concerned, vaginal sex was completely off the table (not to mention the bed). Her husband’s wants and needs had not changed.

Lisa harbored her own resentments. Her husband had gone through several health scares during their time together. He was a type II diabetic, and developed recurring lung abscesses that were eventually traced to a fungal infection. Lisa had sat by his side in hospital beds and nursed him back to health on three separate occasions. She felt betrayed when she saw he had no intention of returning the favor.

They couldn’t stay on a tandem bike together, and they couldn’t stay in a happy marriage. In February of 2017, the couple separated, though they salvaged a cordial relationship for the sake of their step-grandchildren.

The Quest for a Cure

Although Lisa had been physically, financially, and emotionally devasted, she was not about to succumb to resentment and depression. True to character, her first impulse was to fight back.

First, she needed a place to stay. She spent fifteen months living with her daughter and grandchild in the Bay Area. She started making the rounds of doctor’s offices, trying to find some specialist who could tell her what she had, and how to treat it. She wriggled in fabric stackable chairs while waiting for urologists, neurologists, and gastroenterologists.

Her situation invited feelings of powerlessness, but Lisa always came to her doctor’s appointments prepared. She kept records of all her previous visits and procedures, and wore skirts without underwear. She would tell the doctor, “No, you don’t have to leave the room,” when it was time for the physical exam. “Let’s fucking get this over with.”

These appointments mostly resulted in half-hearted diagnoses, and suggestions that Lisa visit a psychological therapist. Never mind that Lisa was already seeing a therapist, and had been doing so for years. And never mind that therapy sessions did nothing to treat her sitting pain (though they were helpful in other ways).

Lisa soon wizened up, and learned to ask question before booking an appointment months in advance. A doctor in the Bay Area once referred her to another clinic for pain management. Before scheduling anything, Lisa called and asked the staff whether they had ever treated pudendal neuralgia. The answer was an uncertain, “No,” and Lisa decided to look elsewhere.

Through the Health Organization for Pudendal Education (HOPE) Lisa learned about a doctor in Phoenix who specialized in the treatment of pudendal neuralgia. The location wasn’t ideal, but for Lisa, the expense and discomfort of travel was worth it, if it meant she could talk to a doctor who could do more than speculate.

In November 2017, the Phoenix doctor made her pudendal neuralgia diagnosis official. He also laid out a lengthy, and unproven course of treatment.

In 2018, Lisa made five trips to Arizona and spent over $20,000 on travel expenses and treatments. She underwent injections of numbing agents, steroids, and Botox. The injections served different purposes, and the doctor used different techniques to deliver the medications. But each procedure involved sticking sharp needles into sensitive areas.

Some of the injections helped – the nerve blocks lasted about six weeks, and her first injection of Botox stopped the pain on her left side. (Her right side, however, got worse.) But despite all the hassle and expense, Lisa was still in too much pain to resume normal life.

She wasn’t opposed to trying treatments outside the mainstream either, and experimented with a number of alternative practices. She tried acupuncture, chiropractic care, LED light therapy, and a hyperbaric chamber (in which patients breathe in extra oxygen at high pressure). None of these lived up to their promises.

In mid-2018, Lisa moved in with her mother and stepfather in Eugene, Oregon. There were worse solutions; Lisa’s son lived nearby, and her daughter Tressa made frequent trips to the Northeast for work. Her other daughter, Sandy, brought her son for frequent visits. The only downside was living in a house with too many chairs and not enough couches.

In Eugene, Lisa assembled a medical team that could provide her with answers and auxiliary treatment. In her search for a new primary care provider, Lisa made an appointment with a nurse practitioner who happened to be an expert on pudendal neuralgia.

The nurse practitioner took Lisa’s diagnosis seriously, and wrote referrals for additional care. After two years of pudendal nerve pain, Lisa had developed a secondary condition: pelvic muscle dysfunction. This, too, would require regular attention.

In for a Shock

Back in Eugene, Lisa could barely move. Driving was out of the question, so she relied on her son to ferry her to medical appointments. She needed a rolling walker to move over ground that was less than perfectly flat. If she walked up or down an incline, her pelvic muscles would go into intense spasms.

Though she had had limited success with her treatments thus far, Lisa found a device she wanted to try. Through her research, she discovered dorsal root ganglion stimulators. These electrical devices are implanted in a person’s back, while a handheld controller allows the patient to control the pattern and intensity of the electrical signals.

The electrical impulses supplied to the cluster of nerves just outside the spinal column is supposed to disrupt the pain signals sent to the brain.

Although dorsal root ganglion stimulators are widely used to treat a variety of pain conditions, their effectiveness in treating pudendal neuralgia was not well studied.

Lisa’s doctor at the pain management clinic hadn’t used it for patients with pudendal neuralgia before, but he consulted with colleagues at other hospitals, studied up on the procedure, and agreed to try. He scheduled the procedure at the end of December, 2018. Squeezing the procedure into the end of the year saved Lisa from the $4,000 copay.

Within a few hours after the device was implanted, Lisa knew she’d made the right decision. Her pain hadn’t disappeared entirely, but Lisa estimated she saw an 80% improvement. She was so thrilled, she agreed to provide a testimonial for the medical device company.

Moving Ahead

Obviously, 80% is not 100%. Lisa still has constant pain, and spends her days managing her condition. She regularly goes to pelvic floor physical therapy, and has learned to do some manual release of the muscles herself. She can’t sit down without inviting a flare-up.

But she can now drive for short distances with the aid of cushion. She can stride down the sidewalk without the use of her walker. And if she’s careful, she can spend a few hours playing with her five-year-old grandson.

She’s lost many parts of her life – cycling, her job, and her husband – that she used to enjoy, and admits it’s been a tough journey. “I never got to suicidal,” she said, “but I’m sometimes okay with not waking up the next day.”

But usually she focuses on the fight ahead. Her current battle is getting Amtrak to provide reasonably-priced cross-country travel to people with disabilities. (Because of an ear injury, Lisa can’t fly even if she could sit.) She says, “They only offer a 10% discount for those with disabilities. They should have a bigger discount for disabled people, but they’ve been really rude about it.”

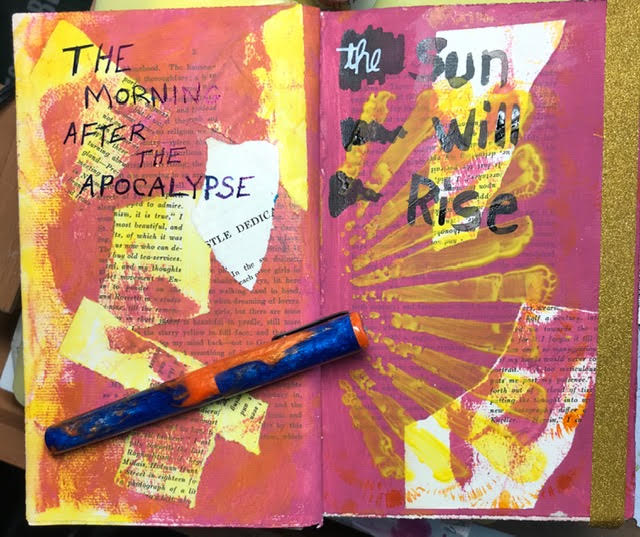

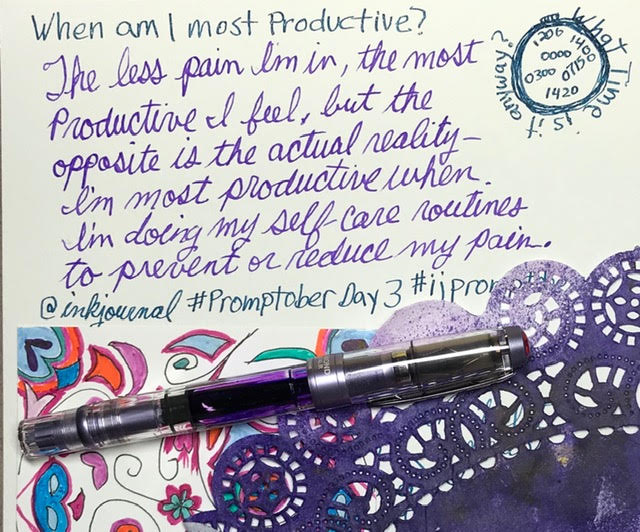

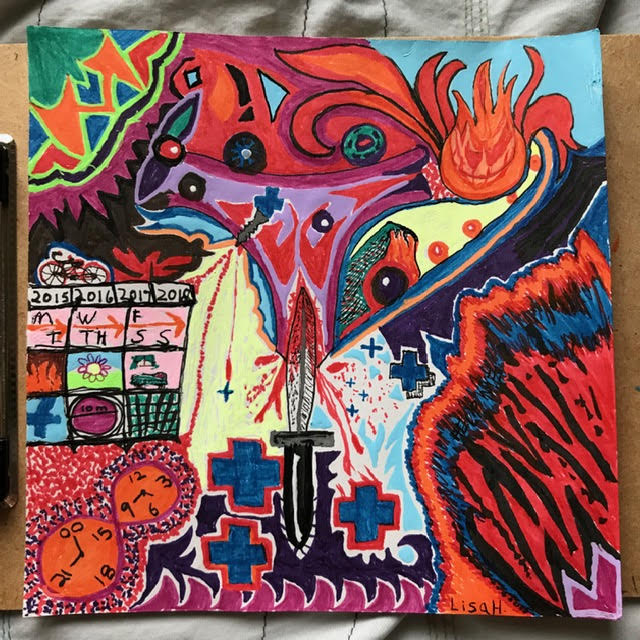

She’s learned that she can get by with less stuff, and dispersed most of her belongings to thrift stores and eBay buyers. She realized she can cook less, and eat just as healthfully. She’s also started drawing with fountain pens, and many of her pictures show what pudendal neuralgia means to her. Swirls of color and curse words are necessary.

My daughter continues to amaze me with her relisiancy and with her love. She has not always used her intelligence wisely as a teen; speed and crashes are hardest on the parent, I thought. Now I see her growth. The ‘drug bust’ does need clarification though. It was a police invasion to arrest my brother who was staying with me, with my permission when he was ‘paroled’, on probation for drug issues/no sales. It was time for his probation officers vacation so Don was handed off to the local police who interpreted it as a good time to investigate the entire web of contacts starting with his sister. It would not have happened if we had social services IN the police department. Yes, Lisa’s mom, me, is and has always been political about personal rights.

Barbara, thanks so much for the clarifying details. The “police invasion,” as you call it, sounds like a frustrating experience, and I can certainly understand how it left a bad taste in your mouth.

As a fellow sufferer of Pudendal Neuralgia I had to leave a comment on your story. Each line I read I thought to myself, yes that’s me , that’s me.

I have suffered with it for nearly 10 years now. It came on following a hysterectomy front and back prolapse. This was all fine vaginally. I’m so pleased you found something that works for you. Regards Marion. Uk.

Marion, I’m so sorry you’ve been dealing with this for 10 years. If I’ve learned anything from writing these stories, it’s that pudendal neuralgia is not for the faint of heart!

Beautifuly written heartbreaking story .perfect balance of humour and precise technical terms . you are my new hero , telling the story people may resist but essential for the teller to say out

Word up

Thank you for sharing your story! You are indeed a hero! And I am so sorry you went through all these! I wish you only the best from now on.