In the two years after my sitting problems started, I visited 13 doctors and specialists. I was looking for an explanation of why I was the way I was, but my hopes were dashed at every turn. All of these highly-trained professionals seemed surprised by my symptoms, and couldn’t find any reason for my inability to sit. At the time, I assumed that I had some rare disease that was outside the bounds of common medical knowledge.

Imagine my surprise, then, when I discovered that back problems are linked to sitting pain, in the same way that rain is linked to mud.

I recently finished wading through Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation by Dr. Stuart McGill. While it wasn’t exactly light reading (Back Mechanic is a better choice there), it did clear up some long-standing (ha!) questions about when and why sitting is bad for backs.

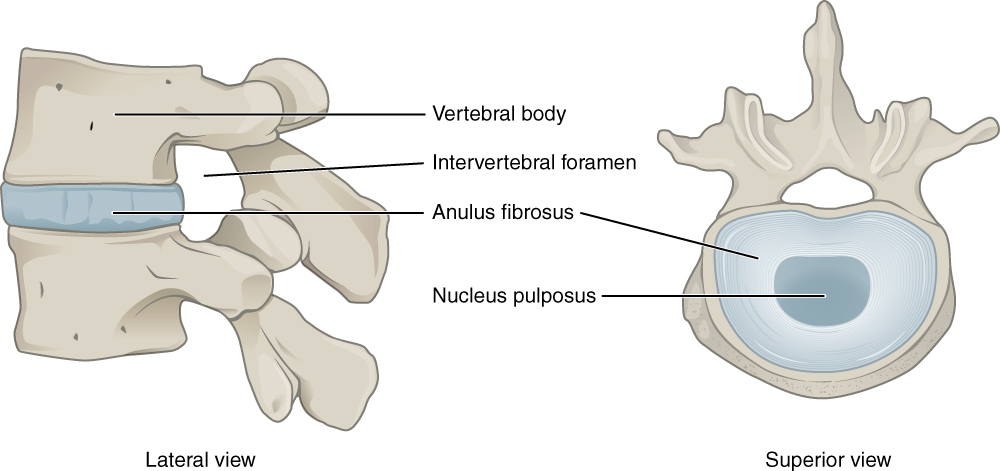

Disc Anatomy

When my doctor was trying to explain my MRI results, he compared my disk to a jelly doughnut. It had a tough outer layer, and a squishy, gelatinous inside.

A better dessert analogy would a lava cake. McGill notes that there is a gradation between nucleus and annulus, but no clear boundary between the two.

I will quote McGill on the character of the nucleus, not because it is particularly relevant, but because it’s one of my all-time favorite pieces of academic prose: “At the risk of sounding crude, the best way to describe a healthy nucleus is that it looks and feels like heavy phlegm. During in vitro testing, we have had it squirt out under pressure and literally stick to the wall.”

What Causes a Disc to Herniate?

Discs permit the spine to bend. In order to do that, they deform, and absorb certain stresses. I couldn’t find a good picture to illustrate this, so instead I used a marshmallow and two Oreos. (I like to keep the dessert theme going.)

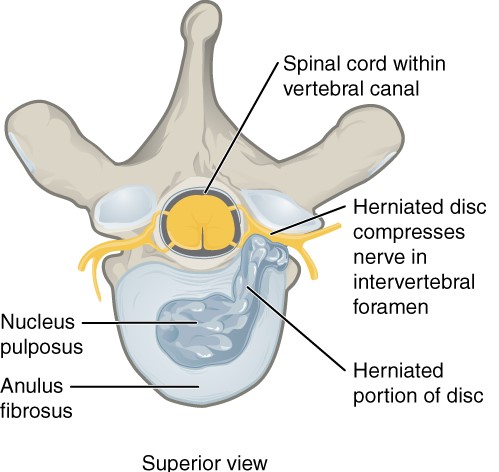

As you can imagine, a lot of bending (especially if there’s extra weight on the spine) will eventually damage the disc. The layers of the annulus will be pulled apart, and the nucleus will be pushed out.

McGill notes that herniations appear to be the result of cumulative trauma, which usually involves a combination of compression (something pressing down on the spine), and flexion (bending forward). The chain of destruction usually begins when some compressive force damages the end plate, which changes how forces are transferred inside the disc. Afterwards, repeated bending can lead to herniation.

As McGill puts it, “[H]erniation of the disc seems almost impossible without full flexion, and without some compressive load.”

This explanation synchs nicely with my own story. A couple of months before my sciatica revved up, I started going to a new gym. The main advantage that the new gym had over my old gym was squat racks. Since every internet fitness plan stresses the importance of squats, I figured I couldn’t be fit without squats.

Did it occur to me that this was maybe a bad idea, considering I can’t even squat down to pick up a quarter?

No. It did not.

When I wasn’t at the gym, I was sitting, either at the office, in the car, or at home.

…Sitting and weighted squats are both on my list of things I don’t do anymore.

Genetic Factors and Disc Damage

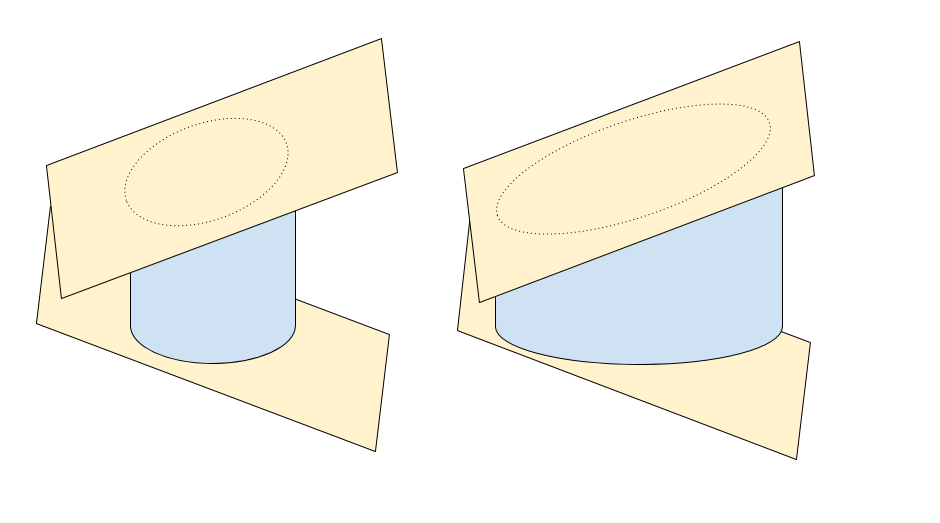

Not everyone’s discs have the same shape. Some people’s discs are shaped like ovals, while other people’s discs are shaped like lima beans (a shape known as “limaçon”). Also, the width of each disc varies from person to person. Each type of disc behaves well in some situations and badly in others.

Oval discs are better-suited to twisting, since they don’t concentrate forces in particular regions like bean-shaped discs do. Limaçon discs are better at bearing compressive loads (like a barbell on the shoulders), but since they concentrate forces in particular areas, they are not well-suited to bending or twisting.

Wider discs are better at absorbing compressive forces (think of football linemen), but because they are wider, the edges of the disc have to compress more on one side, and stretch more on the opposite side, to allow the same degree of movement. And so, wider discs will herniate more readily than thinner discs.

McGill writes, “There is a reason big athletes (with large-diameter limaçon-shaped discs) who generate very high stress can bear the stress without injury, but do poorly with activities such as yoga. Also, these athletes cannot hit a golf ball far because they bend and twist poorly. The archetypical golfer’s spine is slender with ovoid discs that bend and twist with less stress, but it cannot survive high compressive loads.”

Herniated Discs and Sitting

Sitting places the spine in flexion, which exacerbates a disc bulge. There is also an association between sitting and disc herniations, although sitting alone does not appear to be causative. (As noted above, some sort of compression injury also seems to be necessary.)

Because spinal flexion is really the culprit, other forward-bending activities can make a disc bulge worse. Personally, I noticed that putting on my socks and getting pans out of the bottom cabinet also felt uncomfortable.

The stresses placed on the disc and ligaments also change depending on the time of day. Discs absorb water and expand when a person is lying down to sleep at night. Because of these changes, the pressure on the disc is more extreme when bending in the morning, compared to bending in the evening. This means that the risk of injury (or exacerbating an existing injury) is higher in the morning.

However, discs shrink fairly quickly upon rising. Over half of the total loss of disc height happens in the first half hour. McGill recommends waiting an hour before doing anything (such as exercising, driving, gardening, etc.) that requires bending.

Can Herniated Discs Recover?

Yes. Well, sort of. Disc bulges do shrink over time, often in just a few years. However, no one is completely sure how or why this happens. Also, disc herniations appear to be a young person’s problem. The discs in young spines contain more water, and behave differently under pressure than do the comparatively drier discs of older people. That’s not to say older people don’t damage their discs – they do – but the pattern of damage is different.

In some cases (those where at least 70% of the disc height remains), extension can help push the nucleus material back toward the center. This is why McKenzie exercises are helpful to many patients. However, McGill notes that the relatively extreme extension used in McKenzie exercises stresses the facet joints and ligaments, and can lead to other spine problems over time.

There is also no point in doing several repetitions in quick succession. It won’t be any more therapeutic, but it will speed up the disc’s deterioration.

Instead of McKenzies, McGill recommends a posture in which patients lie face-down on the floor and place a hand under their chin. Then, they can place one, or both fists,* under their chin, and hold the position for three minutes.

I have a comparatively rare condition known as a neural underhook, so instead of a fist under my chin, I lie down with a pillow under my hips.

*The goal isn’t to create maximum extension in the spine, the goal is to find the position that’s most comfortable. Putting your chin on two stacked fists isn’t necessarily better that using one fist, or a flat hand.

Flexion Intolerance and Imaging

I remember having a certain discussion with several of my doctors. The doctor would point out that there was nothing worrisome about my MRI, and I’d remark that of course the MRI was fine, because the test was taken while I was lying down, which is a perfectly comfortable position for me. Each time, the doctor would wave away my concerns. Their opinion, it seemed, was that a little thing like posture was unlikely to make a difference.

After reading Low Back Disorders, I feel vindicated.

McGill writes, “I see case after case in which the radiology was simply bogus. For example, a patient with a dynamic disc bulge that grows with flexion postures should sit flexed for a few minutes prior to the image acquisition. Failure to do this results in a bona fide patient being told he has no problem.”

Smug as I feel, I should also point out that McGill does not think imaging scans are necessary, except for out-of-the-ordinary situations, such as when the doctor suspects a tumor. In his opinion, a proper clinical examination is usually more helpful in actually treating the patient.

That may be true, but I posit that skilled clinicians are in a much shorter supply than MRI scans.

The information in Low Back Disorders was revelatory for me. It taught me how to handle my own spine, and gave me a glimmer of hope. (My disc extrusion will probably not continue to get worse until I die. Unless I die really soon. In which case, I will stop worrying about my disc extrusion.)

But there is another psychological benefit. I finally have a creation story to explain why I feel the way I feel. There used to be a blank space in my mind that followed the question, “Why?”. Now, that space has a sketch instead.

One thought on “Sitting and Back Pain: What’s the Connection?”